The US Goes to Town on the Brown

Eat Issue 16: Sweet

This article was originally published in November 2003.

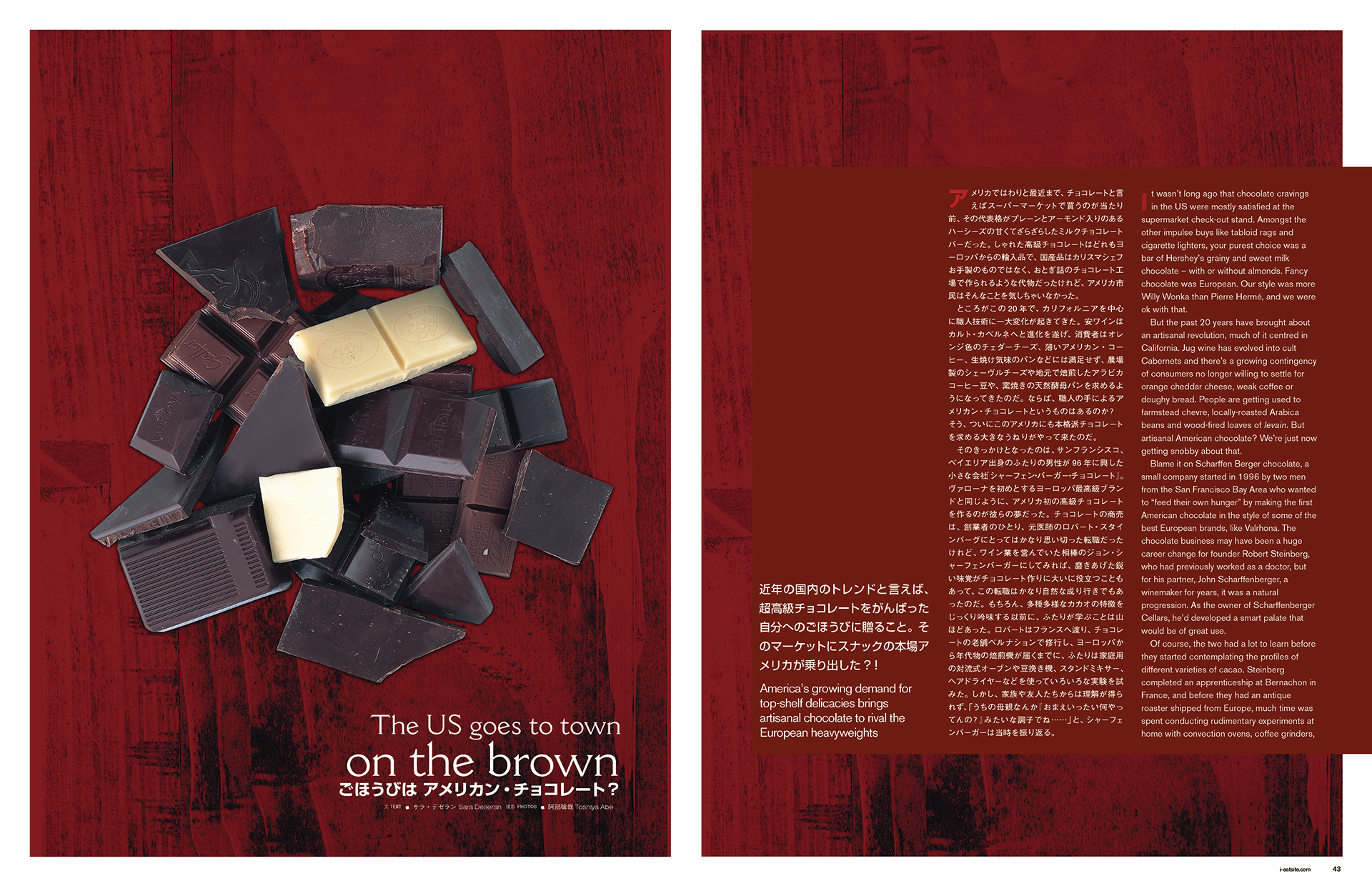

America’s growing demand for top-shelf delicacies brings artisanal chocolate to rival the European heavyweights

It wasn’t long ago that chocolate cravings in the US were mostly satisfied at the supermarket check-out stand. Amongst the other impulse buys like tabloid rags and cigarette lighters, your purest choice was a bar of Hershey’s grainy and sweet milk chocolate – with or without almonds. Fancy chocolate was European. Our style was more Willy Wonka than Pierre Hermé, and we were ok with that.

But the past 20 years have brought about an artisanal revolution, much of it centred in California. Jug wine has evolved into cult Cabernets and there’s a growing contingency of consumers no longer willing to settle for orange cheddar cheese, weak coffee or doughy bread. People are getting used to farmstead chevre, locally-roasted Arabica beans and wood-fired loaves of levain. But artisanal American chocolate? We’re just now getting snobby about that.

Blame it on Scharffen Berger chocolate, a small company started in 1996 by two men from the San Francisco Bay Area who wanted to “feed their own hunger” by making the first American chocolate in the style of some of the best European brands, like Valrhona. The chocolate business may have been a huge career change for founder Robert Steinberg, who had previously worked as a doctor, but for his partner, John Scharffenberger, a winemaker for years, it was a natural progression. As the owner of Scharffenberger Cellars, he’d developed a smart palate that would be of great use.

But artisanal American chocolate? We’re just now getting snobby about that.

Of course, the two had a lot to learn before they started contemplating the profiles of different varieties of cacao. Steinberg completed an apprenticeship at Bernachon in France, and before they had an antique roaster shipped from Europe, much time was spent conducting rudimentary experiments at home with convection ovens, coffee grinders, stand mixers and hair dryers. Not surprisingly, their friends and family were skeptical.

Scharffenberger remembers, “My mother was like, ‘What the hell are you doing?’” But seven years later, the duo are feeling pretty smug – and with good reason. Pastry chefs across the country now namedrop Scharffen Berger like a socialite says Prada. And Guittard, a longtime chocolate maker in San Francisco, has released a new, high-end line called E. Guittard, arguably the only American chocolate in Scharffen Berger’s league for now.

These premium products have made a splash with the hardcore foodies, who have started to describe chocolate in terms once reserved for wine. Adam Smith, of Fog City News in San Francisco, is one example in the extreme. For his shop, where he sells around 200 chocolate bars from around the globe, he conducts "formal sit-down tastings" with his staff to discuss aroma, flavour and texture. For the Scharffen Berger 70% bittersweet, he uses words like “tart raspberry,” “burnt wheat toast” and “flash of brown sugar.” And that’s just to start.

Pastry chefs across the country now namedrop Scharffen Berger like a socialite says Prada.

Over and over, John Scharffenberger has found that people want to make a direct correlation between his old craft and his current one. And there are some strong parallels: chocolate and wine are both fermented, and tannins and acids play a big role in their flavour makeup. Still, the connection that resonates the most is a logical one. Just as wine is only as good as the grapes it’s made with, chocolate is only as good its beans, which break down into three main categories: criollo, of South American origin, which is considered to have the finest flavour; trinitario, with its mild tannins and a spike of fruit; and forastero, the most common variety, with deep fruit tones and a tannic finish.

But this is all a generalization. Cacao beans have more variables than grapes, whose varietals are cloned. “There are so many genetic possibilities in a given field of cacao,” Scharffenberger says. Still, there’s been a market trend to produce single varietal chocolate. Although Gary Guittard admits that single bean chocolates are more “interesting” than delicious, his company offers three such bars. Even Scharffen Berger has released some single varietals – despite the former winemaker being on record describing single bean chocolates as “a bit of a wank.” Both makers agree that chocolate is usually best made with a blend of beans, all with their own characteristics, in order to create a more well-rounded flavour.

The fact that the character of cacao beans is even up for discussion is a fair indication that we might take all this good American chocolate for granted one day soon.

In fact, Pierre Hermé has said that Scharffen Berger makes one of the best chocolates in the world. One of the most famous French pastry chefs willing to publicly applaud an American chocolate? If that’s not a sign that things are changing, then nothing is.

Text: Sara Deseran / Photo: Toshiya Abe

Chocolate and wine

One sniff of a ‘sweet’ theme and our chocoholic Creative Director shipped himself off to California earlier this year to poke around their gourmet chocolate scene. He bounded back – a wee bit heavier – enthusing about wine and chocolate pairings. It was the new gourmet buzz, he told us. Single grapes equal single beans, see? And then there’s the terroir. Gastronomic harmony.

So we spoke to Robert Steinberg, the craftsman behind Sharffen Berger chocolate. “Forget about it,” he told us. Chocolate goes best with whiskey. “The sum is greater than the parts when you put whiskey and chocolate together.” How about wine and chocolate? “Forget about it.”

Too late. We’d roped in a couple of culinary experts to guide us through some choice grape/ bean double acts: Adam Smith, Fog City News’ chocolate fanatic who keeps extensive tasting notes on over 600 bars, and Karla Yukari Pratt, the Park Hyatt Tokyo’s erudite sommelier.

What follows is a heavily edited version of their copious notes, beginning with the qualities common to chocolate and wine. These pairings may or may not be the gastronomic apogee, but they tasted alright to us.

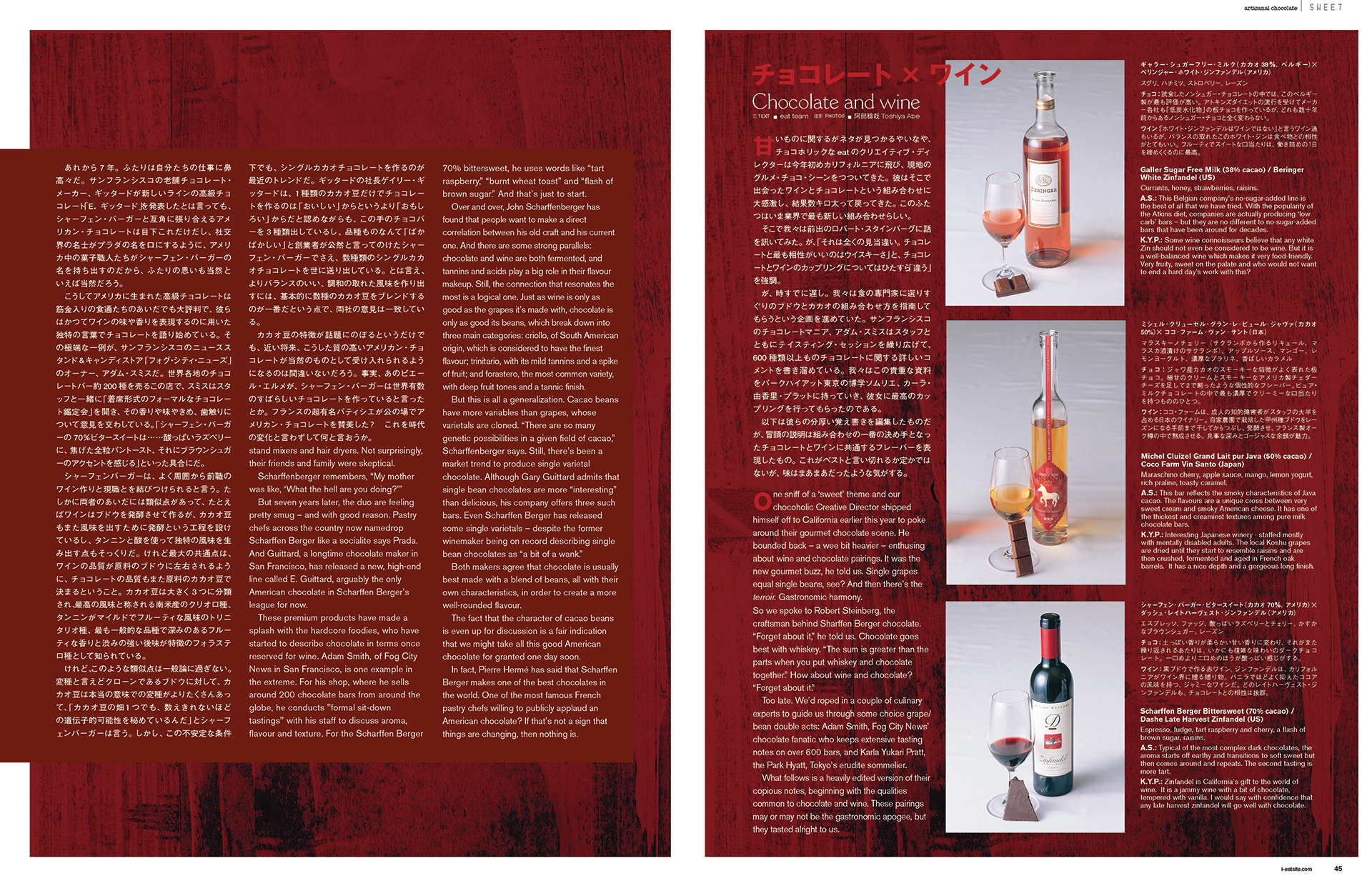

Galler Sugar Free Milk (38% cacao) / Beringer White Zinfandel (US)

Currants, honey, strawberries, raisins.

A.S.: This Belgian company’s no-sugar-added line is the best of all that we have tried. With the popularity of the Atkins diet, companies are actually producing ‘low carb’ bars – but they are no different to no-sugar-added bars that have been around for decades.

K.Y.P.: Some wine connoisseurs believe that any white Zin should not even be considered to be wine. But it is a well-balanced wine which makes it very food-friendly. Very fruity, sweet on the palate and who would not want to end a hard day’s work with this?

Michel Cluizel Grand Lait pur Java (50% cacao) / Coco Farm Vin Santo (Japan)

Maraschino cherry, apple sauce, mango, lemon yogurt, rich praline, toasty caramel.

A.S.: This bar reflects the smoky characteristics of Java cacao. The flavours are a unique cross between very sweet cream and smoky American cheese. It has one of the thickest and creamiest textures among pure milk chocolate bars.

K.Y.P.: Interesting Japanese winery - staffed mostly with mentally disabled adults. The local Koshu grapes are dried until they start to resemble raisins and are then crushed, fermented and aged in French oak barrels. It has a nice depth and a gorgeous long finish.

Scharffen Berger Bittersweet (70% cacao) / Dashe Late Harvest Zinfandel (US)

Espresso, fudge, tart raspberry and cherry, a flash of brown sugar, raisins.

A.S.: Typical of the most complex dark chocolates, the aroma starts off earthy and transitions to soft sweet but then comes around and repeats. The second tasting is more tart.

K.Y.P.: Zinfandel is California`s gift to the world of wine. It is a jammy wine with a bit of chocolate, tempered with vanilla. I would say with confidence that any late harvest zinfandel will go well with chocolate.

Text: Eat Team / Photo: Toshiya Abe