Rot or Not

Eat Issue 12: Rotten

This article was originally published in November 2002.

Rot. It’s a process by which an organic substance undergoes chemical changes wrought by microbial activity and loses the cohesion of its parts.

Fermentation. This describes the transformation of an organic substance into simpler components by the action of a micro-organism.

They’re two sides of the same coin, so what’s the difference?

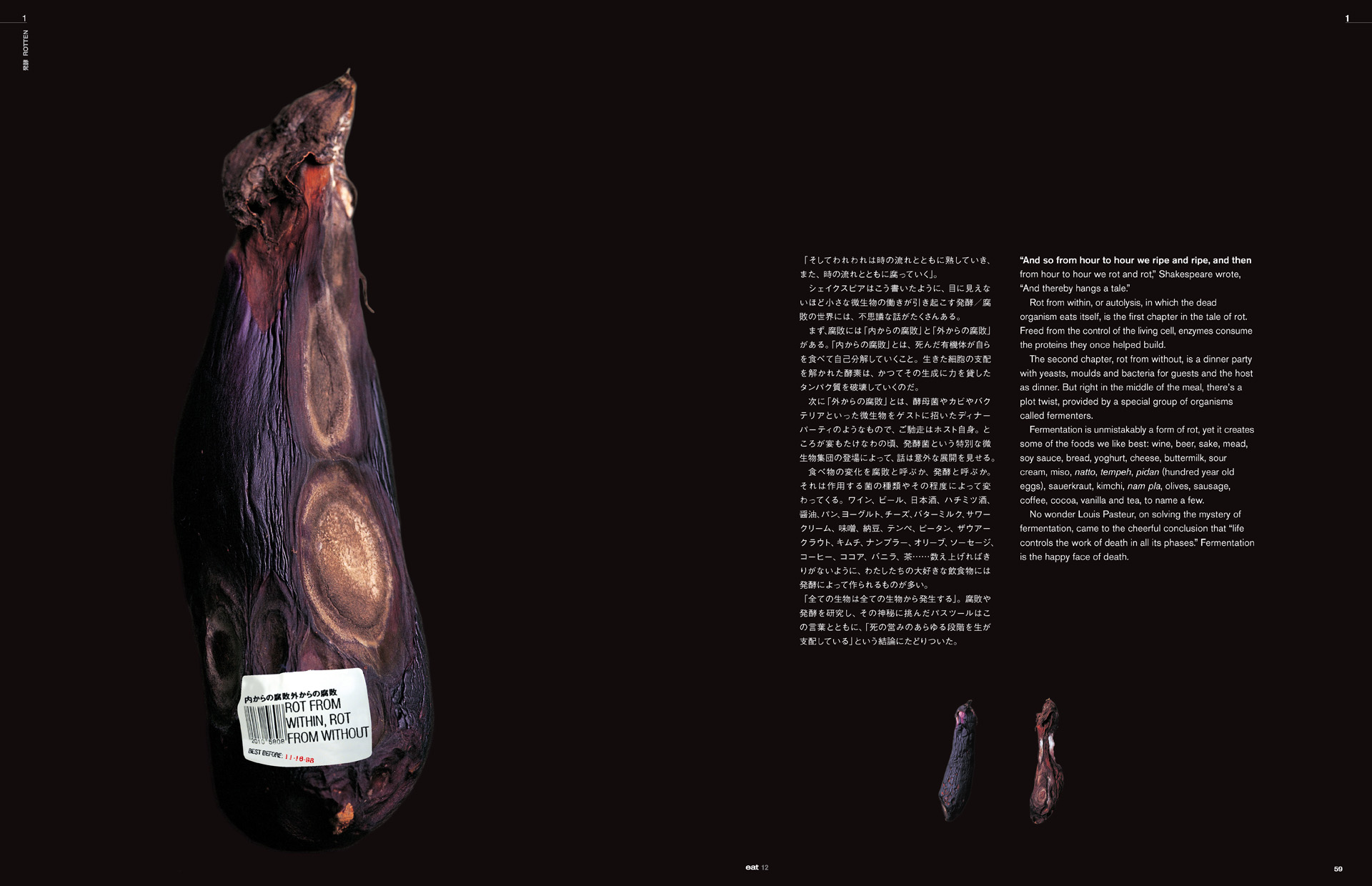

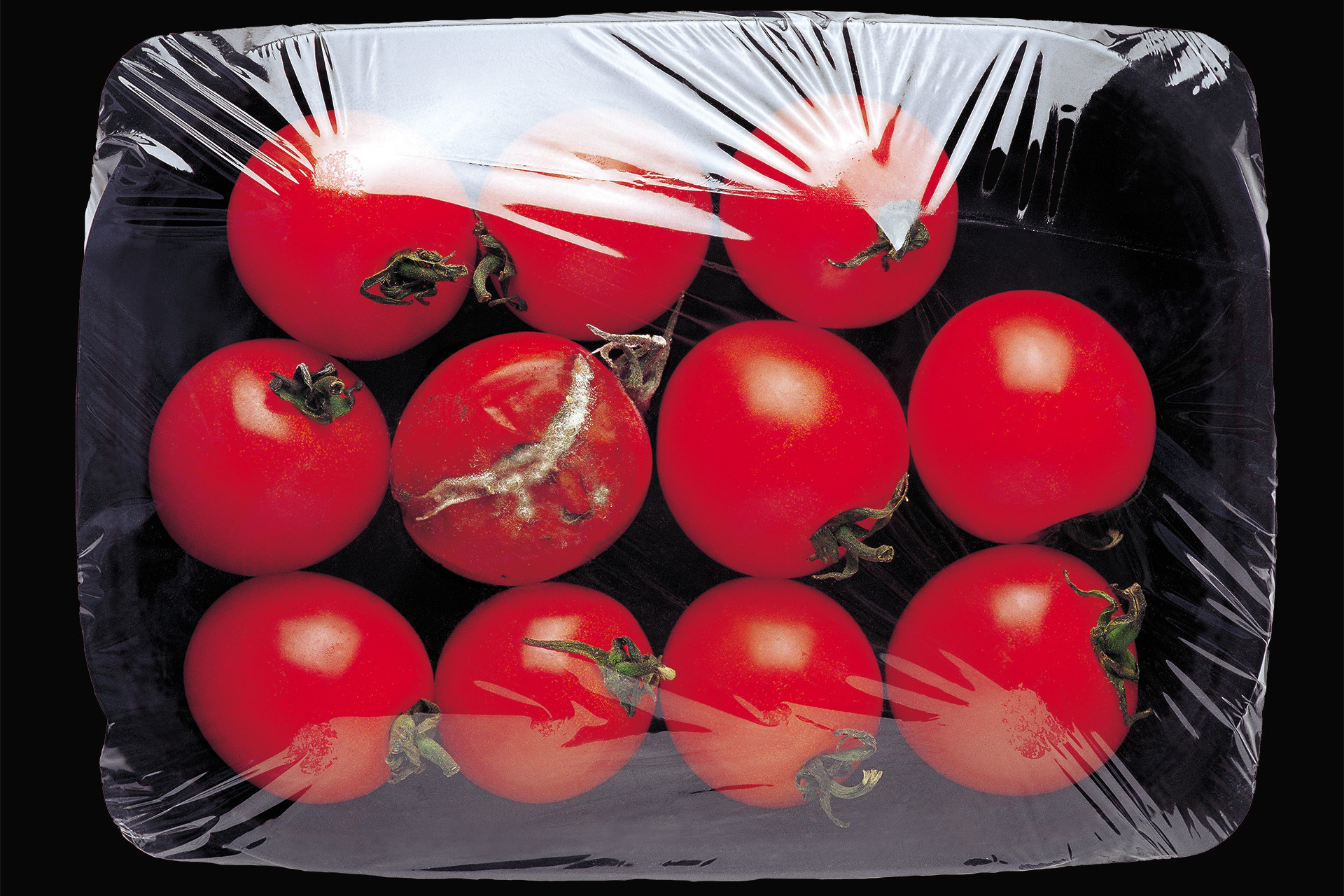

Tomato

Rot from within, Rot from without

“And so from hour to hour we ripe and ripe, and then from hour to hour we rot and rot,” Shakespeare wrote, “And thereby hangs a tale.”

Rot from within, or autolysis, in which the dead organism eats itself, is the first chapter in the tale of rot. Freed from the control of the living cell, enzymes consume the proteins they once helped build.

The second chapter, rot from without, is a dinner party with yeasts, moulds and bacteria for guests and the host as dinner. But right in the middle of the meal, there’s a plot twist, provided by a special group of organisms called fermenters.

Fermentation is unmistakably a form of rot, yet it creates some of the foods we like best: wine, beer, sake, mead, soy sauce, bread, yoghurt, cheese, buttermilk, sour cream, miso, natto, tempeh, pidan (hundred year old eggs), sauerkraut, kimchi, nam pla, olives, sausage, coffee, cocoa, vanilla and tea, to name a few.

No wonder Louis Pasteur, on solving the mystery of fermentation, came to the cheerful conclusion that “life controls the work of death in all its phases.” Fermentation is the happy face of death.

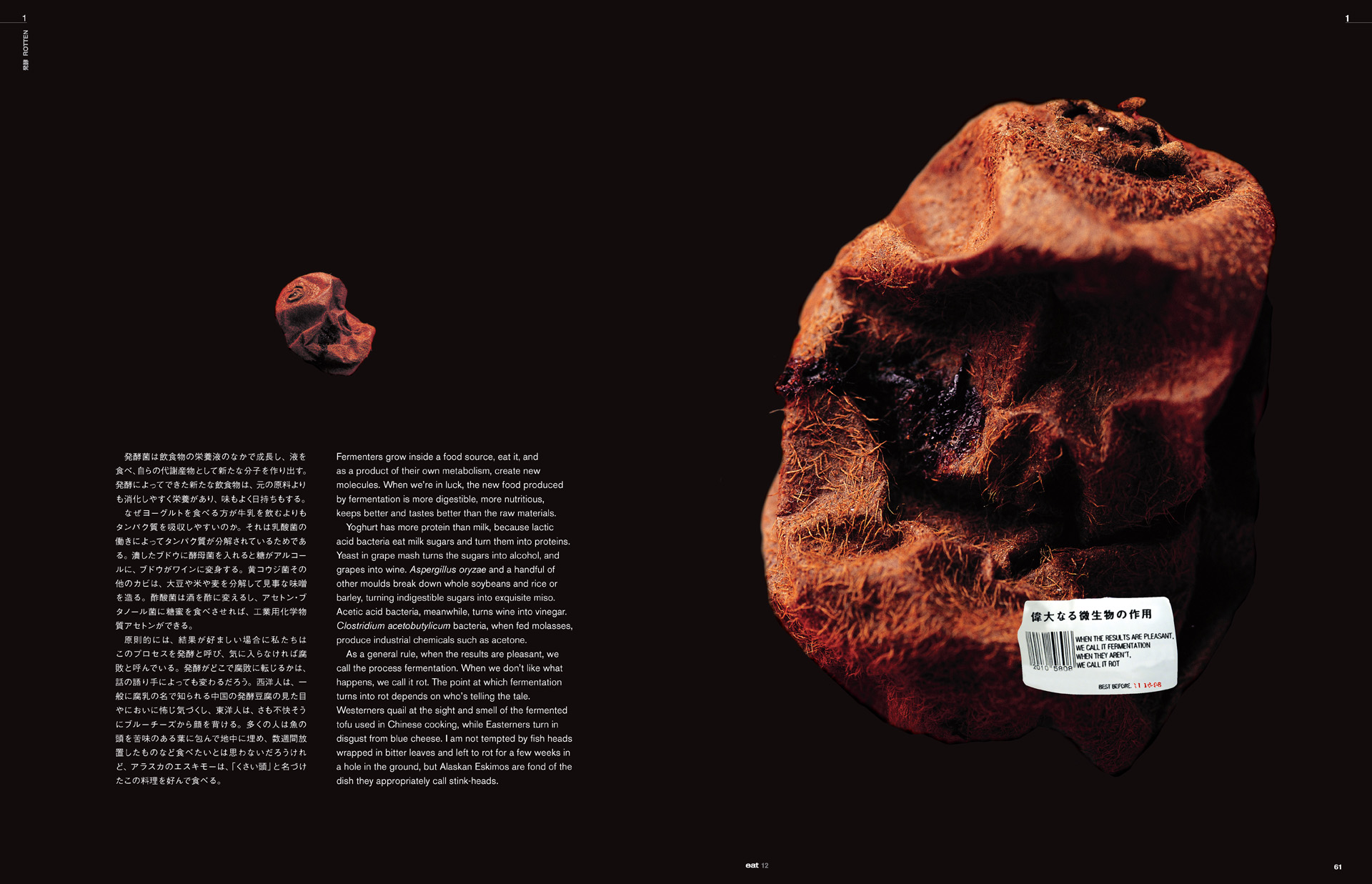

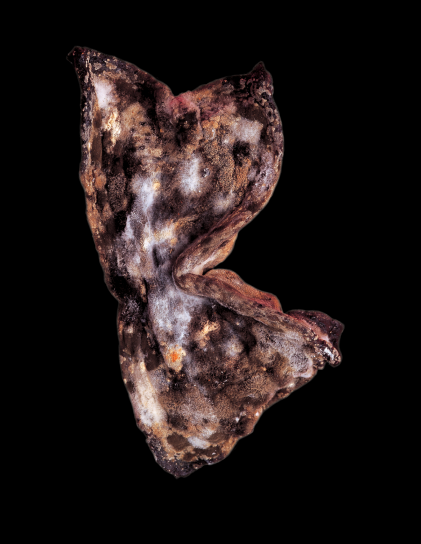

Eggplant

When the results are pleasant, we call it fermentation. When they aren't, we call it rot.

Fermenters grow inside a food source, eat it, and as a product of their own metabolism, create new molecules. When we’re in luck, the new food produced by fermentation is more digestible, more nutritious, keeps better and tastes better than the raw materials.

Yoghurt has more protein than milk, because lactic acid bacteria eat milk sugars and turn them into proteins. Yeast in grape mash turns the sugars into alcohol, and grapes into wine. Aspergillus oryzae and a handful of other moulds break down whole soybeans and rice or barley, turning indigestible sugars into exquisite miso. Acetic acid bacteria, meanwhile, turns wine into vinegar. Clostridium acetobutylicum bacteria, when fed molasses, produce industrial chemicals such as acetone.

As a general rule, when the results are pleasant, we call the process fermentation. When we don’t like what happens, we call it rot. The point at which fermentation turns into rot depends on who’s telling the tale. Westerners quail at the sight and smell of the fermented tofu used in Chinese cooking, while Easterners turn in disgust from blue cheese. I am not tempted by fish heads wrapped in bitter leaves and left to rot for a few weeks in a hole in the ground, but Alaskan Eskimos are fond of the dish they appropriately call stink-heads.

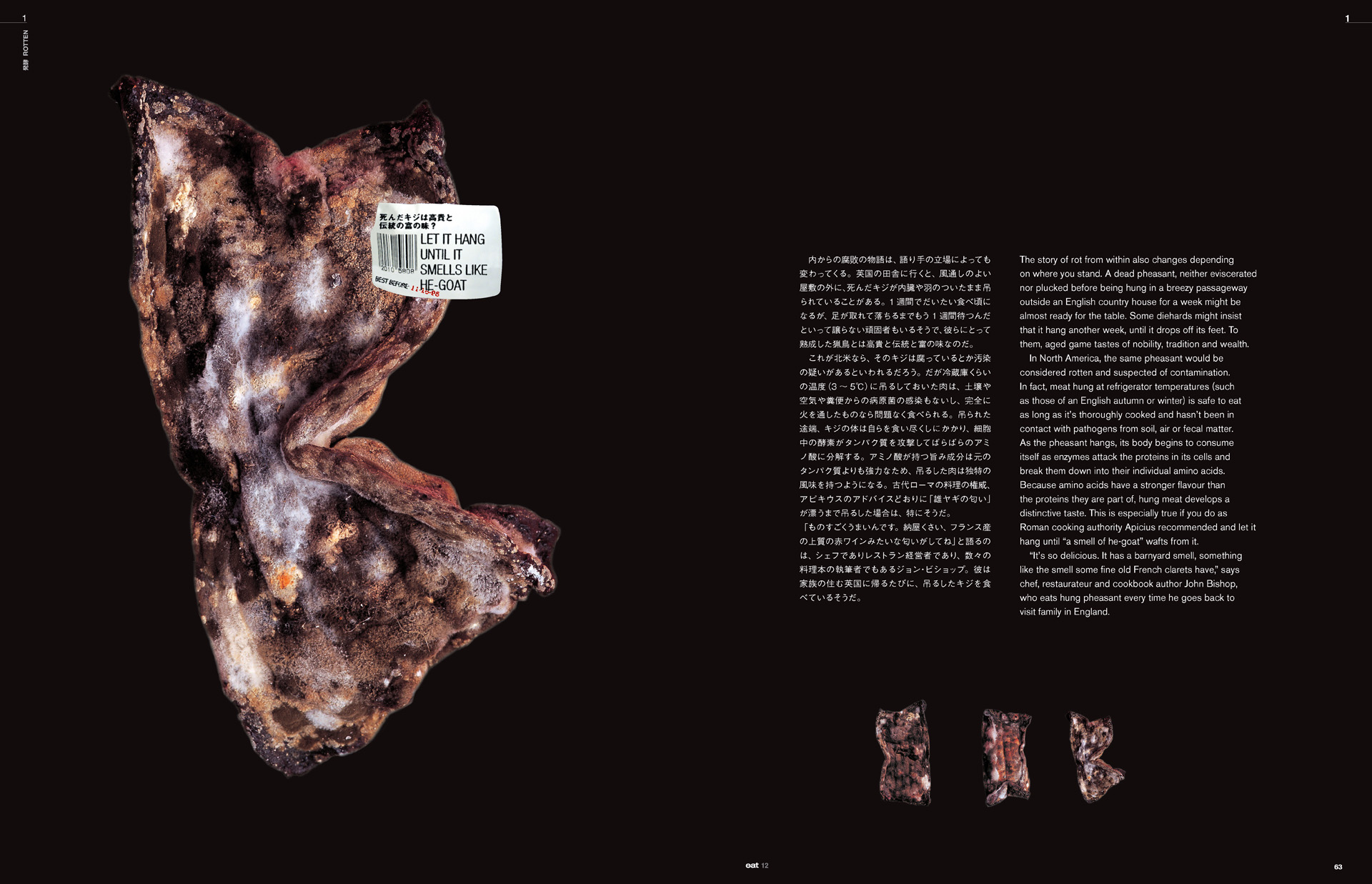

Kiwi

Let it hang until it smells like he-goat.

The story of rot from within also changes depending on where you stand. A dead pheasant, neither eviscerated nor plucked before being hung in a breezy passageway outside an English country house for a week might be almost ready for the table. Some diehards might insist that it hang another week, until it drops off its feet. To them, aged game tastes of nobility, tradition and wealth.

In North America, the same pheasant would be considered rotten and suspected of contamination. In fact, meat hung at refrigerator temperatures (such as those of an English autumn or winter) is safe to eat as long as it’s thoroughly cooked and hasn’t been in contact with pathogens from soil, air or fecal matter. As the pheasant hangs, its body begins to consume itself as enzymes attack the proteins in its cells and break them down into their individual amino acids. Because amino acids have a stronger flavour than the proteins they are part of, hung meat develops a distinctive taste. This is especially true if you do as Roman cooking authority Apicius recommended and let it hang until “a smell of he-goat” wafts from it.

“It’s so delicious. It has a barnyard smell, something like the smell some fine old French clarets have,” says chef, restaurateur and cookbook author John Bishop, who eats hung pheasant every time he goes back to visit family in England.

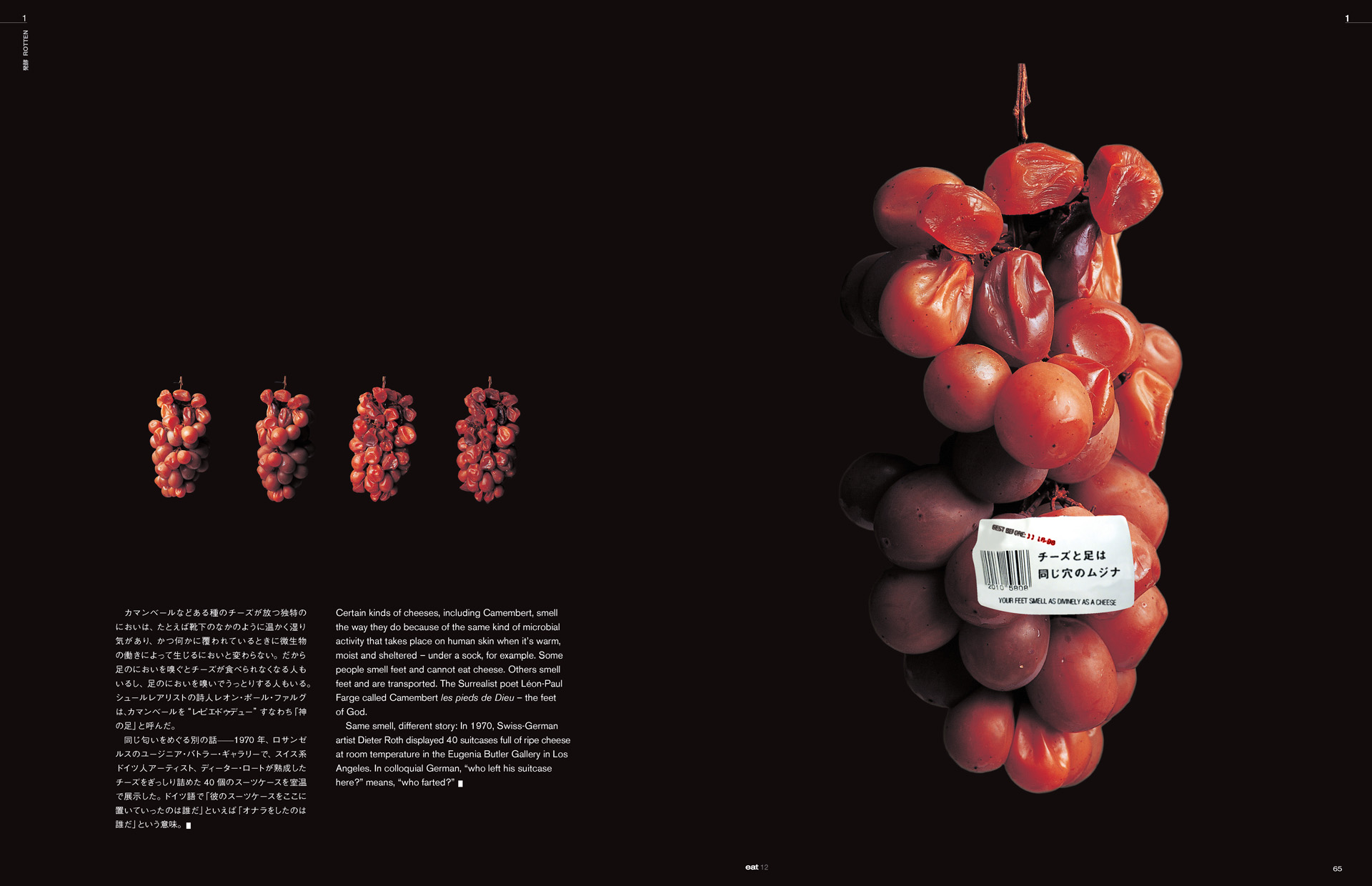

Konyaku

Your feet smell as divinely as a cheese.

Certain kinds of cheeses, including Camembert, smell the way they do because of the same kind of microbial activity that takes place on human skin when it’s warm, moist and sheltered – under a sock, for example. Some people smell feet and cannot eat cheese. Others smell feet and are transported. The Surrealist poet Léon-Paul Farge called Camembert les pieds de Dieu – the feet of God.

Same smell, different story: In 1970, Swiss-German artist Dieter Roth displayed 40 suitcases full of ripe cheese at room temperature in the Eugenia Butler Gallery in Los Angeles. In colloquial German, “who left his suitcase here?” means, “who farted?”

Grapes

Text: Eve Johnson / Photo: Ryohei Baba