Oh, you shouldn't have!

Eat Issue 7: Packaging

This article was originally published in October 2001.

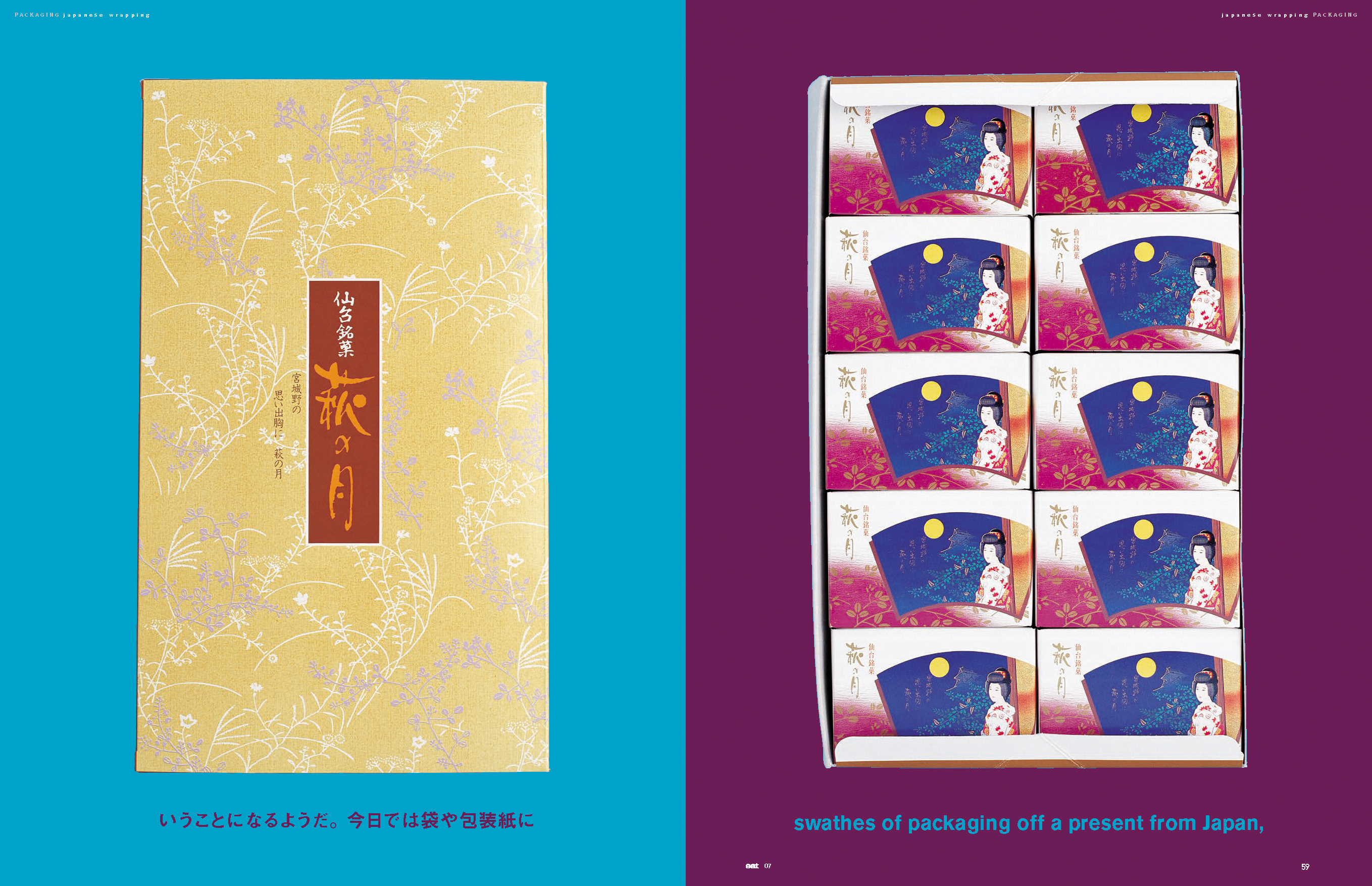

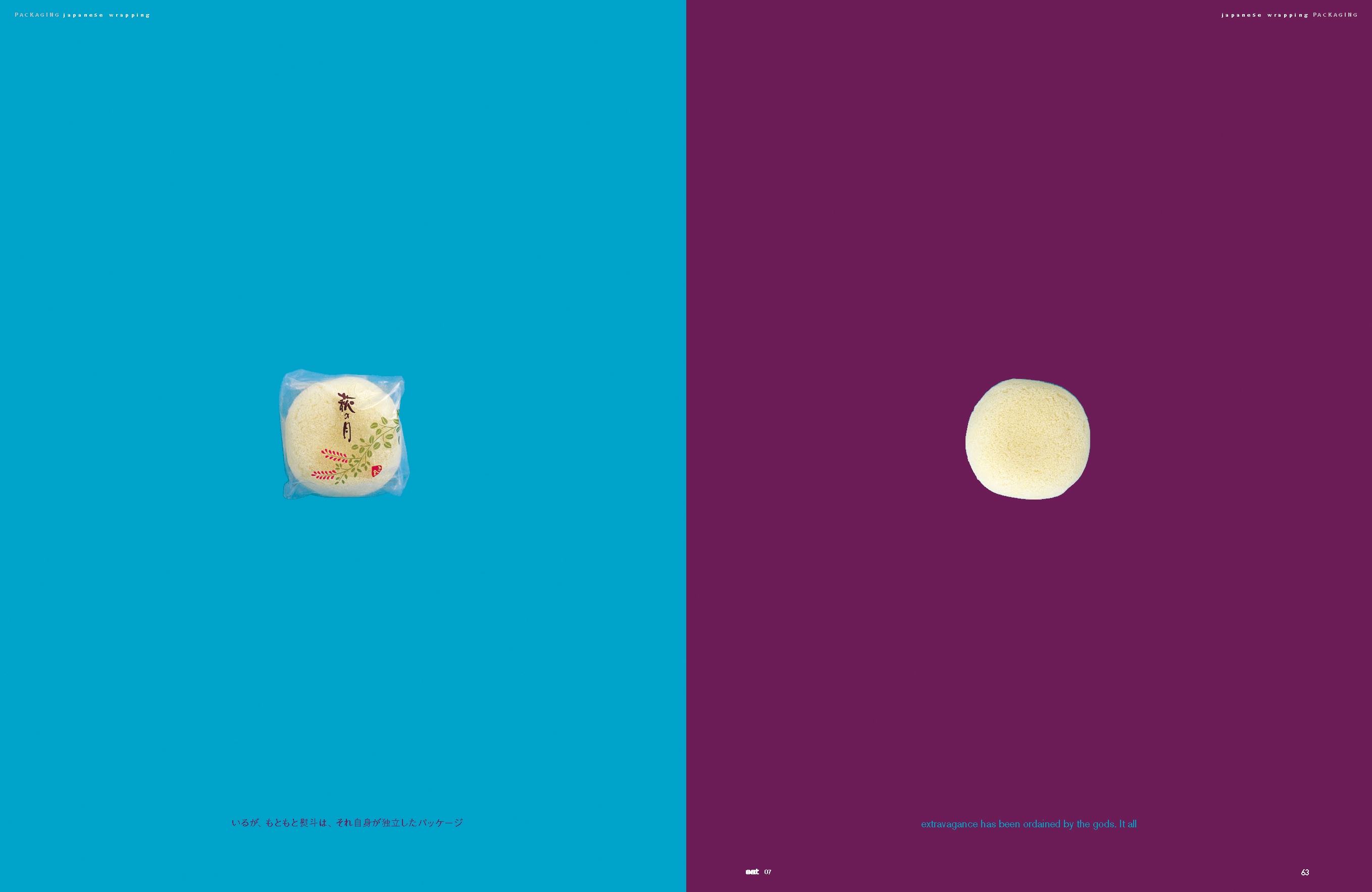

Such beautiful wrapping... but where does it all go? If you've ever felt guilty trashing the swathes of packaging off a present from Japan, it may be some consolation to know that this extravagance has been ordained by the gods.

It all goes back to abalone. In the ancient religion of Shinto, abalone took a proud place on the altar of offerings, probably for the reason that it tastes divine, especially when nibbled between sips of good sake. This is particularly true of noshi abalone in which the meat is sliced, half-dried, stretched, and dried again — a valuable preserved food. Noshi abalone was wrapped in origami, which evolved into a standard colour (yellow) and shape — an elongated hexagon.

Gradually, the folded device itself became known as “noshi,” and continued to accompany gifts even after the inclusion of abalone waned. The small package signified that the object it accompanied belonged to nobody and was, indeed, a gift. It was a declaration of “non-ownership.” This was important to the ancient Japanese, for whom the handling of other people's belongings was taboo. Another belief of the time was that all things housed the spirits of their owners. This is illustrated by a story from the Kamakura period [1185-1333], in which a man receives a gourd as a present. Finding it suspicious, he has a fortune-teller check for good or bad omens inside.

For a present to have maximum meaning, it was necessary to cleanse it of the giver’s attachment. The easiest way to achieve this was to wrap it; a bamboo joint or some kind of hollow cavity; a box; a furoshiki wrapping cloth — all of these closed spaces symbolised the womb, and to put something inside them purified the item of its past and prepared it for rebirth. This belief finds expression in the folk tale Kaguyahime, in which a fallen angel is reborn from a bamboo joint as a princess.

The ritual of wrapping extended as far as money, and even today Japanese avoid giving unwrapped cash. A tip is always enclosed in a special money envelope, or wrapped in a piece of calligraphy paper. The custom is not limited to formal gifts — even if you are simply bringing food to a neighbour, a dishcloth is placed on top of the dish. When you give children a snack, you wrap it in paper and twist the packet closed. Wrapping is part of everyday life.

Some people played with this paradox. A man in the Edo period once bribed the government official Rojyu Tanuma with a few lowly sand whiting. On the surface, this was an absurd, meager gift for such a fat cat. But the giver had taken pains to send, along with his fish, some yuzu citrus for garnish and a stunningly carved small sword with which to peel them.

The penchant for wrapping persists. Non-Japanese may be perplexed by the insistence of convenience-store clerks, on being instructed not to bag a purchase, still to attach a piece of the store’s tape. Apart from showing proof of purchase, this too is part of the ritual, of cleansing the object and relinquishing ownership. It is the only way that things can change hands. For better or worse, Japanese stuff is destined to be wrapped.

Text: Muneharu Takayama / Photo: Ayumi Moriyama