From Palate to Palette

Eat Issue 3: Art or Food?

This article was originally published in February 2001.

From the earliest times, food has figured as a central theme in art. Why, and what does it mean? In a piece specially written for Eat magazine, leading art critic Martin Coomer looks back through the ages to give us a potted history of food and the visual arts.

From the humblest of fare to the most flamboyant feast, food has maintained a constant, widely interpreted presence in the history of art. The connection between food and art can be seen as far back as the Ancient Egyptians, who made myriad depictions of lavish banquets and offerings to the gods. In western art, biblical themes involving the symbolic exchange of foodstuffs have dominated for centuries; versions of ‘The Last Supper’ are still being made today, for example. Still life painting, which came into its own in 17th-century Holland and Spain, is often more than a document of life’s staple ingredients, just as genre painting, the depiction of everyday domestic scenes, is loaded with symbolism. As a signifier of purity or evil, proof of social status, or a vehicle for social satire, food is densely woven into an ever-evolving series of coded messages.

Let’s start then with the most symbolically loaded food of all, the apple. The temptation of Adam and the banishment from the Garden of Eden provides the subject for countless masterpieces of western art. In the 16th century Albrecht Durer and Lucas Cranach the Elder both gave an uncanny, and at the time shocking, likeness to Adam and Eve. In Hugo van der Goes’ ‘The Fall of Man’ (c1470), Eve reaches to pluck a second apple from the tree, having already taken a bite of the first. Meticulous detail, typical of Netherlandish painting of the 15th century, adds a disquieting intensity to the image.

The enduring capacity of this humble fruit to strike our consciousness is remarkable. When, in 1966, Yoko Ono left an apple to rot on a plinth, her action was intended to demonstrate the Fluxus movement’s doctrine of object as fact, not symbol. Except of course that the apple is undeniably loaded. John Lennon recognised this. Visiting her show at the Indica Gallery, New York, he took a bite. Later Ono made a cast in bronze of a bitten apple. Was she claiming mythic status for their relationship? Even today, in the photographs of Austrian artist Erwin Wurm, the apple packs a mighty, almost subliminal, punch. While Wurm’s photograph of a young man who, with a whole apple lodged in his mouth, stares proudly to camera is laugh-out-loud funny, are we not transported back to the Garden of Eden?

Giuseppe Arcimboldoʼs ʻThe Gardener (A Joke with Vegetables)ʼ, circa 1590. The painting can be turned upside down. Courtesy of Erich Lessing/PPS.

On another level Wurm is an heir to Surrealists such as Ren Magritte, whose love of the bizarre juxtaposition harks back to the work of the 16th-century painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo. To enter the world of Arcimboldo is to enter a greengrocer’s delight. Employed by a series of Hapsburg emperors, he developed a means of producing human likenesses composed entirely of fruits, flowers, vegetables and other foodstuffs. ‘Summer’ (1573) is a profile portrait of fecundity; cherries, grapes and plums form a bristling mane, while a ripe peach becomes a dimpled cheek. Biting satire also enters the equation: his face composed of meat and fried fish and his eye that of a plucked chicken, ‘The Lawyer’ (1566) is a truly hideous sight; turned upside down ‘The Gardener (A Joke with Vegetables)’ (c1590) becomes a bowl of lowly root vegetables.

Viewed as somewhat silly at the time, these images languished outside the historical canon until taken up by the Surrealists in the 20th century. The Polish-born painter Hans Bellmer was particularly entranced by Arcimboldo’s vivid concoctions. In ‘Milles Filles’ (1939), he creates an elongated female form writhing with masses of fruit and vegetables. Bellmer also makes a pun on the French cake mille-feuille – woman as confection. As recently as 1991 we see the enduring influence of Arcimboldo in Yasumasa Morimura’s ‘Mother’ (1991), a photographic version of a Lucas Cranach painting, depicting the biblical story of Judith. In Morimura’s version, the scene is transformed into a bizarre still life with the artist’s head topped with cabbage leaves, a necklace of Brussels sprouts around his neck.

Light years away from Arcimboldo’s flights of fantasy is the more sober strain of still life painting that was gathering momentum contemporaneously. Religious symbolism weighs heavily in examples such as Gerard David’s ‘Madonna of the Milk Soup’ (c1513). A depiction of the Virgin and child that is both a still life and a landscape, this tiny painting emphasises the reverence of the Madonna’s milk. While this symbolises Mary’s grace, a loaf of bread on the table is a reminder of the Last Supper and an apple signifies the transcendence of sin.

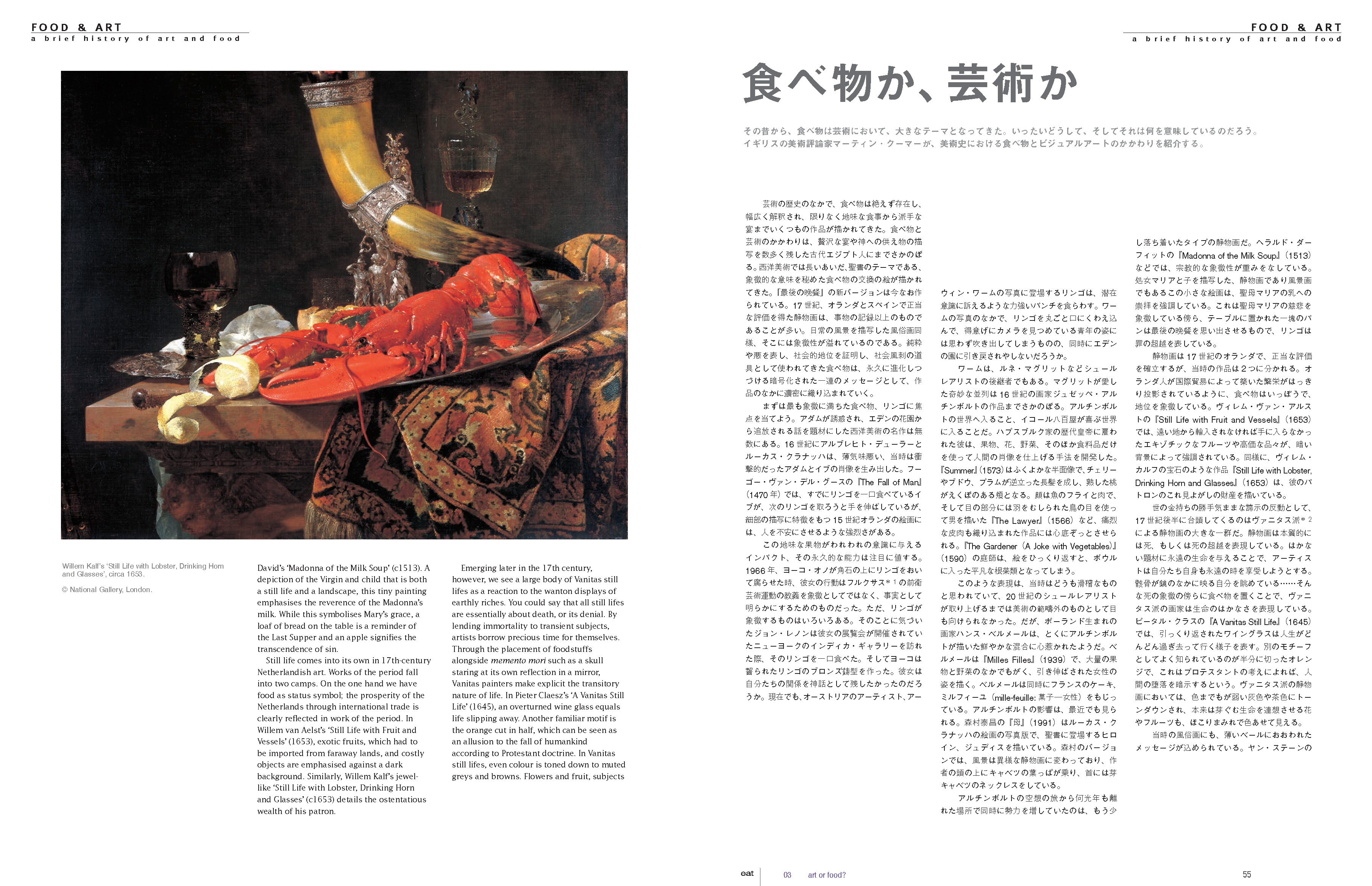

Willem Kalfʼs ʻStill Life with Lobster, Drinking Horn and Glassesʼ, circa 1653. © National Gallery, London.

Still life comes into its own in 17th-century Netherlandish art. Works of the period fall into two camps. On the one hand we have food as status symbol; the prosperity of the Netherlands through international trade is clearly reflected in work of the period. In Willem van Aelst’s ‘Still Life with Fruit and Vessels’ (1653), exotic fruits, which had to be imported from faraway lands, and costly objects are emphasised against a dark background. Similarly, Willem Kalf’s jewel-like ‘Still Life with Lobster, Drinking Horn and Glasses’ (c1653) details the ostentatious wealth of his patron.

Emerging later in the 17th century, however, we see a large body of Vanitas still lifes as a reaction to the wanton displays of earthly riches. You could say that all still lifes are essentially about death, or its denial. By lending immortality to transient subjects, artists borrow precious time for themselves. Through the placement of foodstuffs alongside memento mori such as a skull staring at its own reflection in a mirror, Vanitas painters make explicit the transitory nature of life. In Pieter Claesz’s ‘A Vanitas Still Life’ (1645), an overturned wine glass equals life slipping away. Another familiar motif is the orange cut in half, which can be seen as an allusion to the fall of humankind according to Protestant doctrine. In Vanitas still lifes, even colour is toned down to muted greys and browns. Flowers and fruit, subjects normally associated with burgeoning life, look dusty and faded.

Genre painting of the period also wears a thinly cloaked moral message. In Jan Steen’s ‘As the Old Sing, so the Young Tweet’ (1663-65), a group of bons vivants sets a bad example to their young. Always the party pooper, Steen even invites death to the celebration of birth: in his ‘The Christening Feast’ (1664), the artist has included broken eggs, a well-known symbol of mortality. In England, genre painting becomes a vehicle for a long-standing, often biting satire of the privileged classes. In one of the supreme achievements of British painting, William Hogarth’s six-part ‘Marriage a la Mode’ (1745), the artist paints the folly and the tragedy of human life in things as much as situations. In ‘The Lady’s Death’, the final scene, the setting is a frugal house. By the window a table is laid with a frugal breakfast, a boiled egg set in a dish of rice. An emaciated dog is set to make off with a pig’s head, a spitting image of the dying countess in the nearby bed. Here, Hogarth also parodies the great 18th-century still life and genre painter Chardin, whose paintings transform the simple pleasures of domestic life into scenes of reverential calm.

Jan Steenʼs ʻCelebrating the Birthʼ, 1664. Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the Wallace Collection, London.

During the 17th century still life was also becoming established as a genre in Spain where the Vanitas theme was known as ‘disillusionments of the world’. The starkest confrontations with death, however, can be found in Goya’s still lifes painted around 1810, shortly after he had completed his etchings ‘The Disasters of War’ an unflinching record of the atrocities committed during the ongoing battle with France. Piles of game birds are reminiscent of the corpses of young soldiers heaped up in works such as ‘So Much and More’. With Goya, more than any other artist of the period, one gains a real sense of the dead weight of game and the bloodiness of meat. In the 1930s and ‘40s, the Lithuanian-born painter Chaim Soutine imbued still life with a similar sense of anguish at the tragedy of war. Inspired by Rembrandt’s painting ‘The Slaughtered Ox’ (1655), Soutine painted sides of beef with wild expression; he in fact 57kept both a rotting carcass and buckets of blood in his studio, which he used to ‘freshen’ his subject.

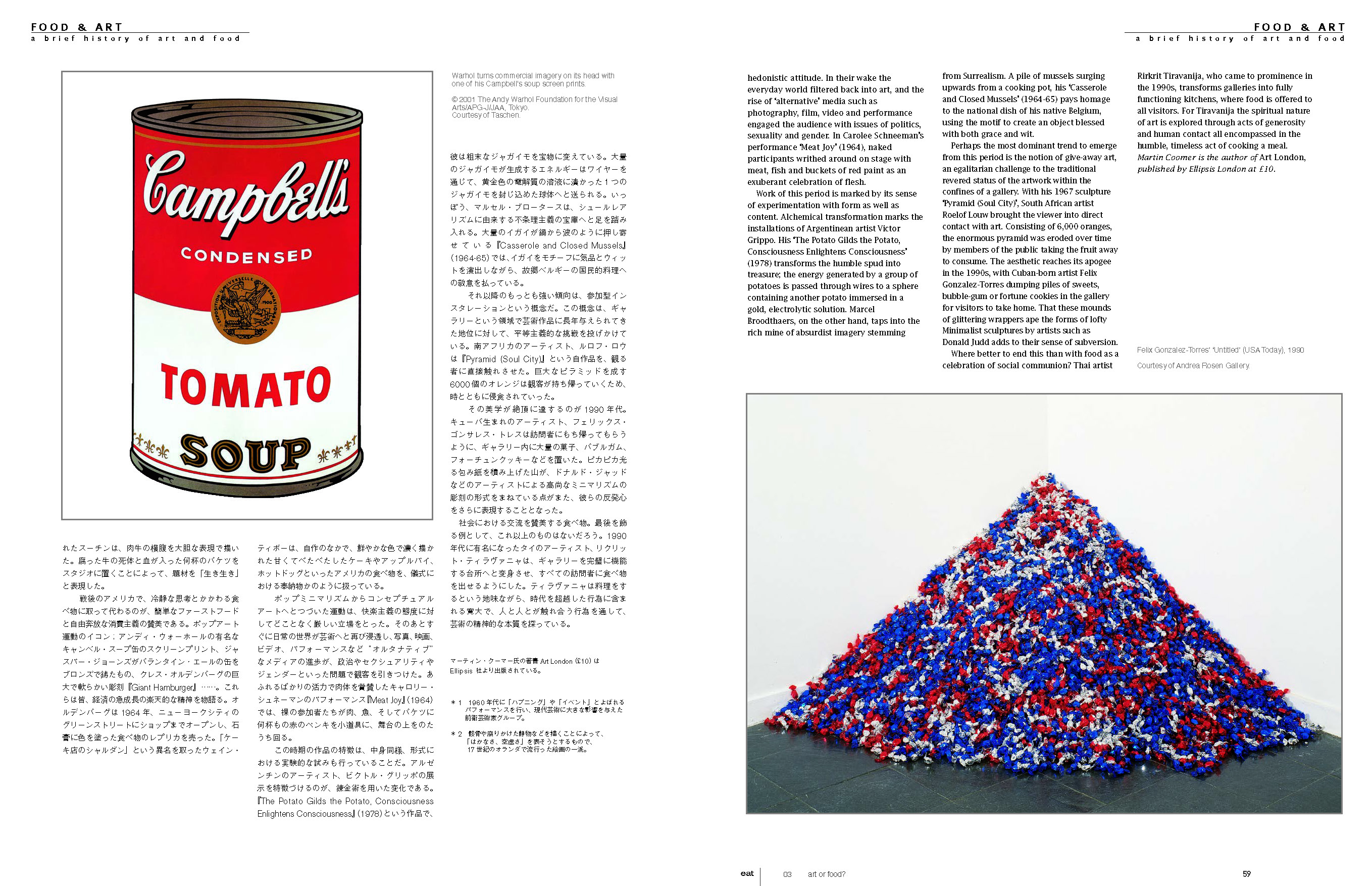

Jump to post-war America, and food for sobering thought is replaced by the quick fix of fast food and a celebration of rampant consumerism. Icons of the Pop Art movement – Andy Warhol’s famous screen prints of Campbell’s soup tins, Jasper John’s Ballantine Ale cans cast in bronze, Claes Oldenburg’s ‘Giant Hamburger’ (1962), a huge, soft sculpture – all attest to the upbeat spirit of economic boom; in 1964 Oldenburg even opened a shop on Green Street, NYC, where he sold painted plaster replicas of food. Wayne Thiebaud has been described as ‘The Chardin of the cake shop’. Thickly painted in bright candy colours, his paintings present a host of all-American foods – gooey cakes, apple pie, hot dogs – as almost ritualistic offerings.

Warhol turns commercial imagery on its head with one of his Campbell's soup screen prints. © 2001 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts/APG-J/JAA, Tokyo. Courtesy of Taschen.

The movements that followed Pop Minimalism and Conceptualism made a somewhat puritanical stand against its hedonistic attitude. In their wake the everyday world filtered back into art, and the rise of ‘alternative’ media such as photography, film, video and performance engaged the audience with issues of politics, sexuality and gender. In Carolee Schneeman’s performance ‘Meat Joy’ (1964), naked participants writhed around on stage with meat, fish and buckets of red paint as an exuberant celebration of flesh.

Work of this period is marked by its sense of experimentation with form as well as content. Alchemical transformation marks the installations of Argentinean artist Victor Grippo. His ‘The Potato Gilds the Potato, Consciousness Enlightens Consciousness’ (1978) transforms the humble spud into treasure; the energy generated by a group of potatoes is passed through wires to a sphere containing another potato immersed in a gold, electrolytic solution. Marcel Broodthaers, on the other hand, taps into the rich mine of absurdist imagery stemming from Surrealism. A pile of mussels surging upwards from a cooking pot, his ‘Casserole and Closed Mussels’ (1964-65) pays homage to the national dish of his native Belgium, using the motif to create an object blessed with both grace and wit.

Marcel Broodthaersʼ ʻCasserole and Closed Musselsʼ, 1964. Courtesy of the Tate Gallery, London.

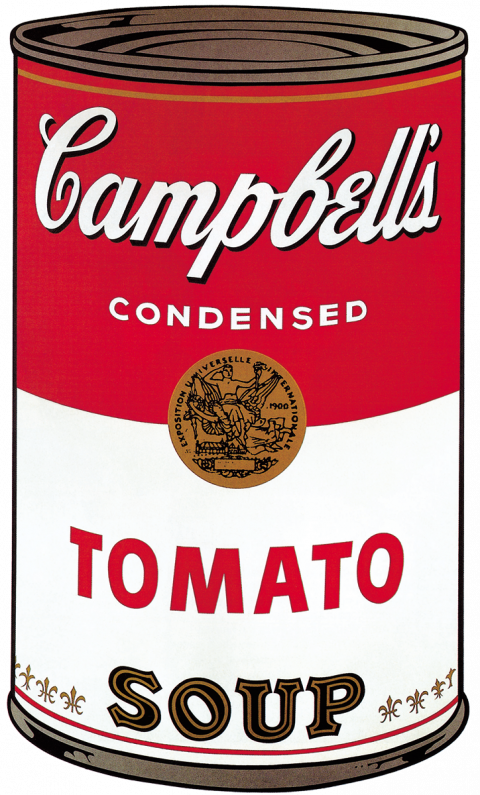

Perhaps the most dominant trend to emerge from this period is the notion of give-away art, an egalitarian challenge to the traditional revered status of the artwork within the confines of a gallery. With his 1967 sculpture ‘Pyramid (Soul City)’, South African artist Roelof Louw brought the viewer into direct contact with art. Consisting of 6,000 oranges, the enormous pyramid was eroded over time by members of the public taking the fruit away to consume. The aesthetic reaches its apogee in the 1990s, with Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres dumping piles of sweets, bubble-gum or fortune cookies in the gallery for visitors to take home. That these mounds of glittering wrappers ape the forms of lofty Minimalist sculptures by artists such as Donald Judd adds to their sense of subversion.

Felix Gonzalez-Torresʼ ʻUntitledʼ (USA Today), 1990 Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery.

Where better to end this than with food as a celebration of social communion? Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, who came to prominence in the 1990s, transforms galleries into fully functioning kitchens, where food is offered to all visitors. For Tiravanija the spiritual nature of art is explored through acts of generosity and human contact all encompassed in the humble, timeless act of cooking a meal. Martin Coomer is the author of Art London, published by Ellipsis London at £10.

Text: Martin Coomer