Feasting with the Dead

Eat Issue 8: Ritual

This article was originally published in December 2001.

Paying respects to ancestors with offerings of food provides a comforting link to the next world, says Tazlu Endo

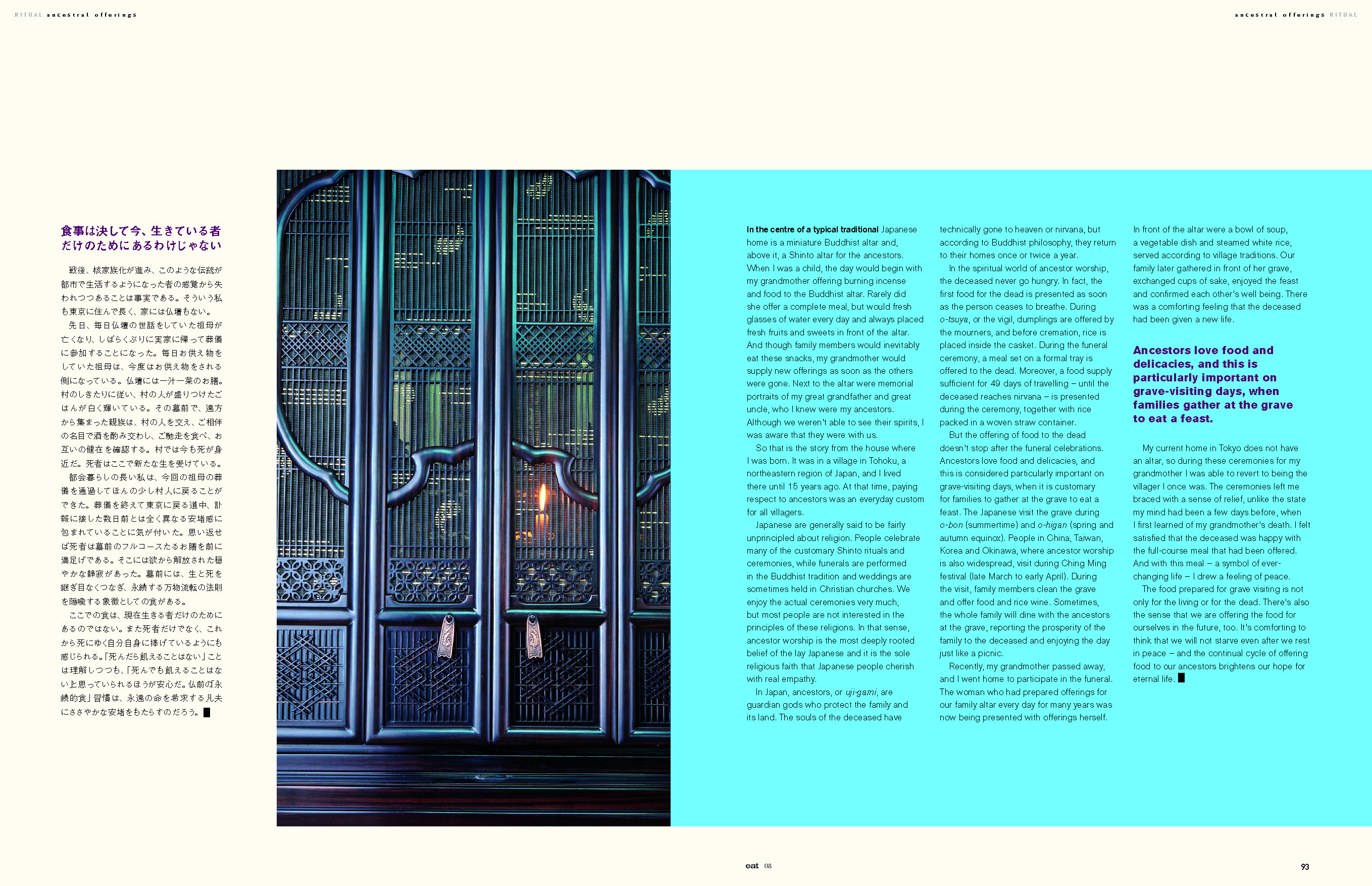

In the centre of a typical traditional Japanese home is a miniature Buddhist altar and, above it, a Shinto altar for the ancestors. When I was a child, the day would begin with my grandmother offering burning incense and food to the Buddhist altar. Rarely did she offer a complete meal, but would fresh glasses of water every day and always placed fresh fruits and sweets in front of the altar. And though family members would inevitably eat these snacks, my grandmother would supply new offerings as soon as the others were gone. Next to the altar were memorial portraits of my great grandfather and great uncle, who I knew were my ancestors. Although we weren’t able to see their spirits, I was aware that they were with us.

So that is the story from the house where I was born. It was in a village in Tohoku, a northeastern region of Japan, and I lived there until 15 years ago. At that time, paying respect to ancestors was an everyday custom for all villagers.

Japanese are generally said to be fairly unprincipled about religion. People celebrate many of the customary Shinto rituals and ceremonies, while funerals are performed in the Buddhist tradition and weddings are sometimes held in Christian churches. We enjoy the actual ceremonies very much, but most people are not interested in the principles of these religions. In that sense, ancestor worship is the most deeply rooted belief of the lay Japanese and it is the sole religious faith that Japanese people cherish with real empathy.

In Japan, ancestors, or uji-gami, are guardian gods who protect the family and its land. The souls of the deceased have technically gone to heaven or nirvana, but according to Buddhist philosophy, they return to their homes once or twice a year.

In the spiritual world of ancestor worship, the deceased never go hungry. In fact, the first food for the dead is presented as soon as the person ceases to breathe. During o-tsuya, or the vigil, dumplings are offered by the mourners, and before cremation, rice is placed inside the casket. During the funeral ceremony, a meal set on a formal tray is offered to the dead. Moreover, a food supply sufficient for 49 days of travelling – until the deceased reaches nirvana – is presented during the ceremony, together with rice packed in a woven straw container.

But the offering of food to the dead doesn’t stop after the funeral celebrations. Ancestors love food and delicacies, and this is considered particularly important on grave-visiting days, when it is customary for families to gather at the grave to eat a feast. The Japanese visit the grave during o-bon (summertime) and o-higan (spring and autumn equinox). People in China, Taiwan, Korea and Okinawa, where ancestor worship is also widespread, visit during Ching Ming festival (late March to early April). During the visit, family members clean the grave and offer food and rice wine. Sometimes, the whole family will dine with the ancestors at the grave, reporting the prosperity of the family to the deceased and enjoying the day just like a picnic.

Ancestors love food and delicacies, and this is particularly important on grave-visiting days, when families gather at the grave to eat a feast.

Recently, my grandmother passed away, and I went home to participate in the funeral. The woman who had prepared offerings for our family altar every day for many years was now being presented with offerings herself. In front of the altar were a bowl of soup, a vegetable dish and steamed white rice, served according to village traditions. Our family later gathered in front of her grave, exchanged cups of sake, enjoyed the feast and confirmed each other’s well being. There was a comforting feeling that the deceased had been given a new life.

My current home in Tokyo does not have an altar, so during these ceremonies for my grandmother I was able to revert to being the villager I once was. The ceremonies left me braced with a sense of relief, unlike the state my mind had been a few days before, when I first learned of my grandmother’s death. I felt satisfied that the deceased was happy with the full-course meal that had been offered. And with this meal – a symbol of ever-changing life – I drew a feeling of peace.

The food prepared for grave visiting is not only for the living or for the dead. There’s also the sense that we are offering the food for ourselves in the future, too. It’s comforting to think that we will not starve even after we rest in peace – and the continual cycle of offering food to our ancestors brightens our hope for eternal life.

Text: Tazlu Endo / Photo: Tsukasa Furusato