F is for Fake

Eat Issue 3: Art or Food?

This article was originally published in February 2001.

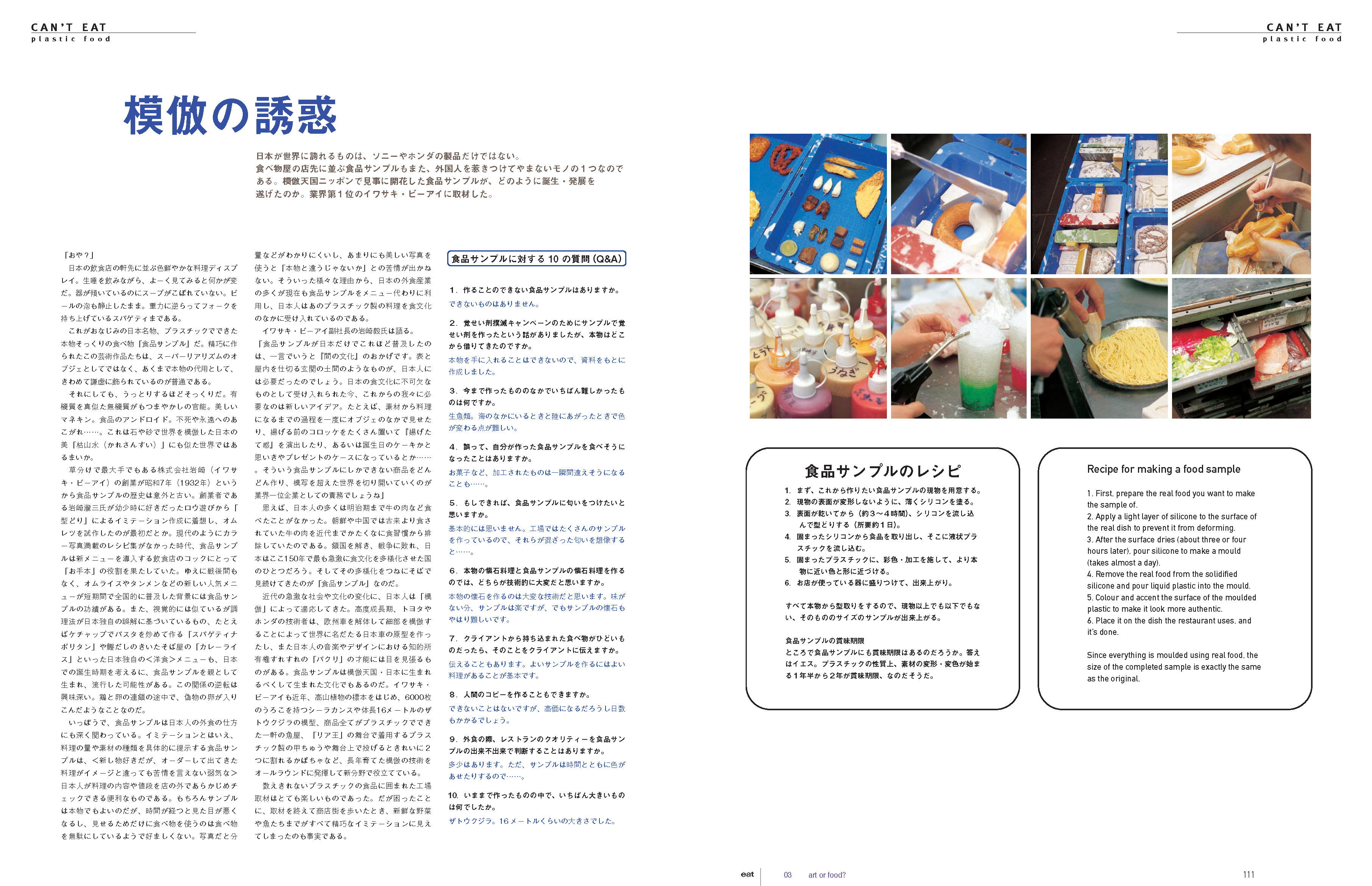

The world of art has long been dogged by fake and forgery. So is the world of food. In Japan, restaurants spend millions of yen producing exquisitely detailed models of their food for display outside. Tazlu Endo meets the men who mould the plastics. Just don’t call them artists.

“What?” Take a close look at the displays of brightly coloured food at the entrances of restaurants in Japan. Something strange is going on. The bowl is tilting, but the soup is not spilled. The froth on the beer is motionless. There is even a gravity-defying fork twirling spaghetti in mid air.

All of these foods are made of plastic, and all seem so real that you have to look twice to be able to tell them apart from the real thing. The resemblance is mesmerising. A fake sensuousness expressed by an inorganic substance imitating the organic. Think of beautiful mannequins, food androids, and our endless pursuit of immortality and eternity.

The industry has a longer history than you might think. The trailblazer and still the biggest company in this field, Iwasaki BI was founded in 1932. It all began when Ryuzo Iwasaki, its founder, made his first sample – an omelette. The reason the idea took off so fast is that Japan at the time was being invaded by new foreign foods, and as chefs did not have access to colour photos of the new dishes, they took to representing them in three dimensions. The boom intensified after the war, and plastic food is largely responsible for the spread in Japan of omelettes and Chinese noodles.

Of course, in the early days, the food produced was startlingly different from what was enjoyed in the West. Spaghetti Neapolitan was made simply by frying pasta with tomato ketchup, curry rice tasted strongly of the fish used in its preparation. Be warned, both of these dishes are based on uniquely Japanese misunderstandings of the original, and both are still available in Tokyo today. As they caught on, rival chefs would steal each others’ menus by copying the plastic models, rather than the recipes. Talk about life imitating art.

Except that it’s not art. Not according to Takeshi Iwasaki, vice president of Iwasaki BI.

“No. It’s certainly not art. We just copy something that’s there. The last thing I need in my factory is an artist. I don’t need interpretations, I want copies.”

The food samples he produces are also closely related to the way the Japanese eat out. The models may just be imitations, but they exactly represent the volume and ingredients of the real dishes. For Japanese people, who love to try new things but are often too timid to complain if the food defies their expectations, the imitations provide a safe way to check ingredients and prices beforehand. For visitors who can’t read Japanese menus, too, it can turn out to be surprisingly handy. Many foreigners survive in Tokyo by escorting the waiter or waitress outside and pointing at what they want to eat.

But what does Iwasaki BI make of it all?

“The reason food samples have become so widespread in Japan is in short, the ‘culture of ma (pause)’,” explains Takeshi Iwasaki. “It was once necessary for the Japanese to have something like an earth-floored room at the doorway, which helped people make a clear distinction between the inside and outside. Now that food samples are fulfilling that role and have been accepted as indispensable in Japanese food culture, we need new ideas. For example, recreating the entire cooking process to illustrate how ingredients transform as a dish is created, or displaying lots of pre-fried croquettes to transmit the message that they are fresh-fried, or making a gift case that looks like a real birthday cake. We believe that it is our responsibility as an industry leader to continue launching unique products and create a new world beyond imitation.”

All very laudable, but with a bizarre side-effect. On leaving the Iwasaki BI factory I passed a fruit and vegetable store. Nothing looked real. I may never trust food again.

Everything you always wanted to know about plastic food. Iwasaki answers our questions.

1. Is there a food sample you can’t make?

No.

2. I heard that you made a sample of drugs for an anti-drugs campaign. Where did you borrow the real drugs?

We cannot obtain the real drugs, so we made them based on available data.

3. What has been the most difficult sample to make?

Raw fish. The colour of a fish brought ashore is different from when it is in the water.

4. Have you ever tried eating the food samples you made by accident?

Sometimes I almost do, with processed food such as snacks.

5. Would you add scent to food samples, if possible?

When I imagine the mixed smell that would be generated by the wide variety of samples we make at the factory… I really don’t think so.

6. Which do you think would be more technically difficult to make, real kaiseki ryori or a sample of it?

The preparation of kaiseki ryori requires great skill. It is not that difficult to make samples, since we do not have to season them. However, kaiseki samples would require skill.

7. If the client provides you with unsatisfactory food, do you tell them?

Sometimes. Good samples are made from good food. That is the basic rule.

8. Is it possible to copy a person?

It wouldn’t be impossible, but it would be costly and time consuming.

9. When you dine out, do you ever judge the quality of a restaurant by how well the food samples are made?

Sometimes. But the colour of food samples fades as time passes, so…

10. What is the biggest thing you have ever made?

A humpback whale about 16 metres long.

11. Does plastic food go off?

Yes. It starts to discolour after 18 months to two years.

Recipe for making a food sample

1. First, prepare the real food you want to make the sample of.

2. Apply a light layer of silicone to the surface of the real dish to prevent it from deforming.

3. After the surface dries (about three or four hours later), pour silicone to make a mould (takes almost a day).

4. Remove the real food from the solidified silicone and pour liquid plastic into the mould.

5. Colour and accent the surface of the moulded plastic to make it look more authentic.

6. Place it on the dish the restaurant uses, and it’s done.

Since everything is moulded using real food, the size of the completed

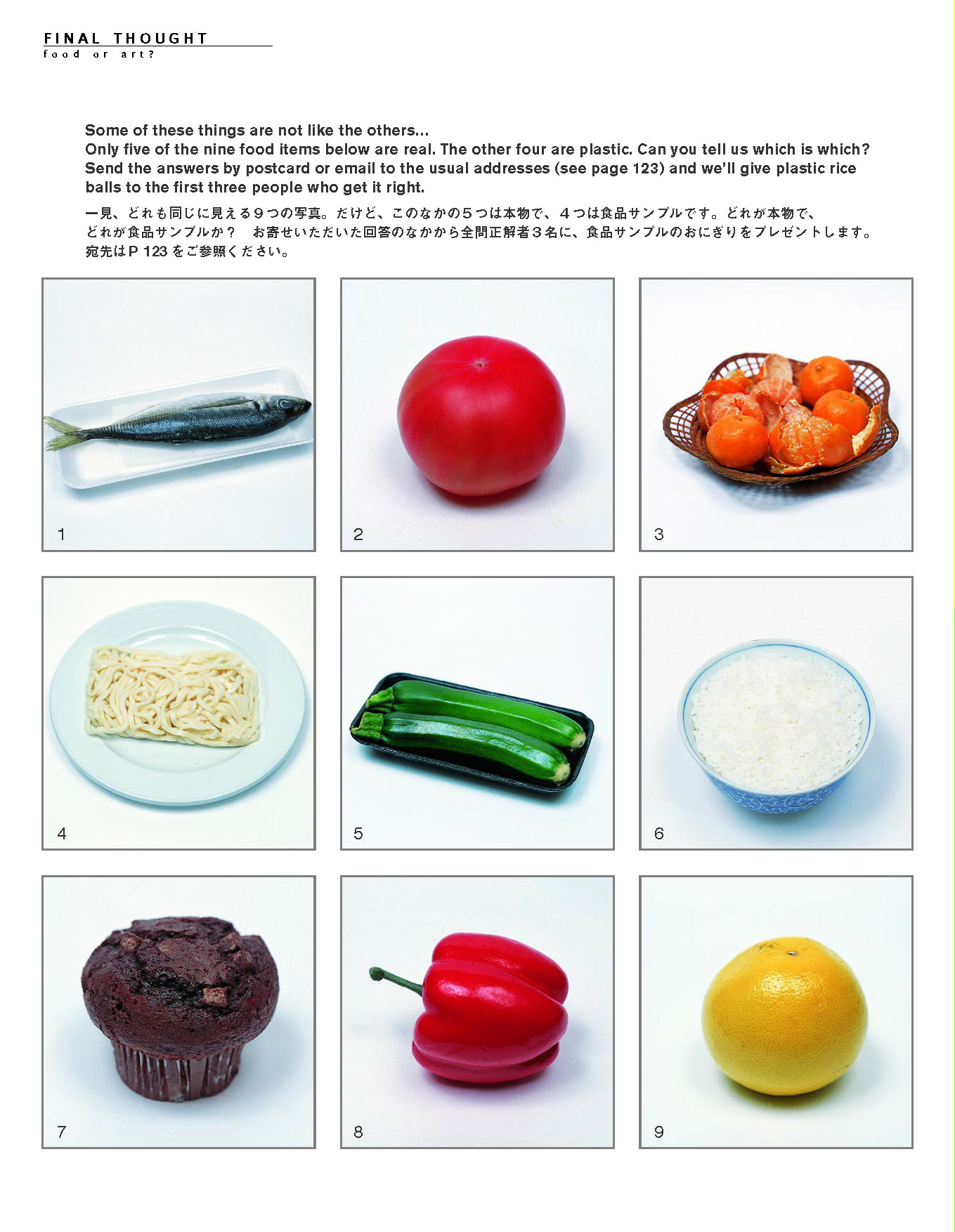

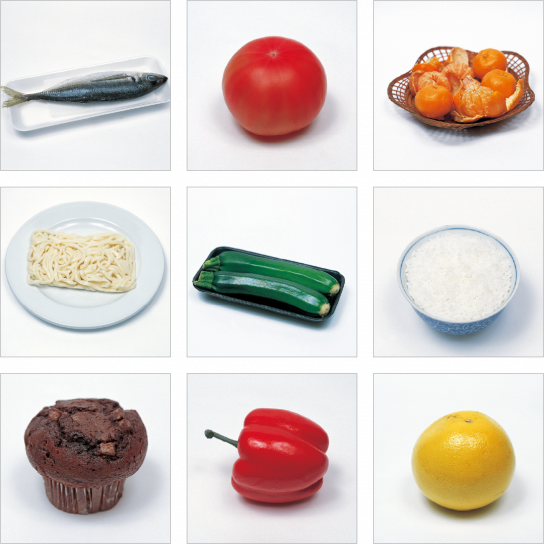

Some of these things are not like the others… Only five of the nine food items below are real. The other four are plastic. Can you tell us which is which?

˙ɹǝddǝd pǝɹ puɐ lʍoq ǝɔᴉɹ 'uɐʞᴉɯ 'oʇɐɯoʇ ǝɹɐ sɯǝʇᴉ ɔᴉʇsɐlԀ :ɹǝʍsu∀

Text: Tazlu Endo / Photo: Toshiya Abe, Satomi Ono