Thinking Differently About Aid In 2025

Aid is big business. In 2023, global ODA (Overseas Development Assistance) totalled US$223.3 billion. Of that, the US contributes 29%, or $64.7 billion. So, when the US pulls the plug, as it did in January this year, the results are immediate and devastating. I got to see this for myself on a field visit to the Thai Myanmar border with REI (Refugee Empowerment International). Here people flee across the border to escape the fighting and bombing by the military government, against the Karen, Karenni and other ethnic groups in Myanmar’s south. Compounding the daily horrors and uncertainty these displaced people experience, we heard of a hospital being closed overnight, and families with permission to resettle in the US, being turned around at the airport with no home to go back to. Written down, it sounds overdramatic, but this is real. There are 120 million displaced people in the world. Their challenges before January were enormous. The cut in aid just made things significantly worse. On our trip we got to meet some of the people who devote their lives to dealing with these challenges.

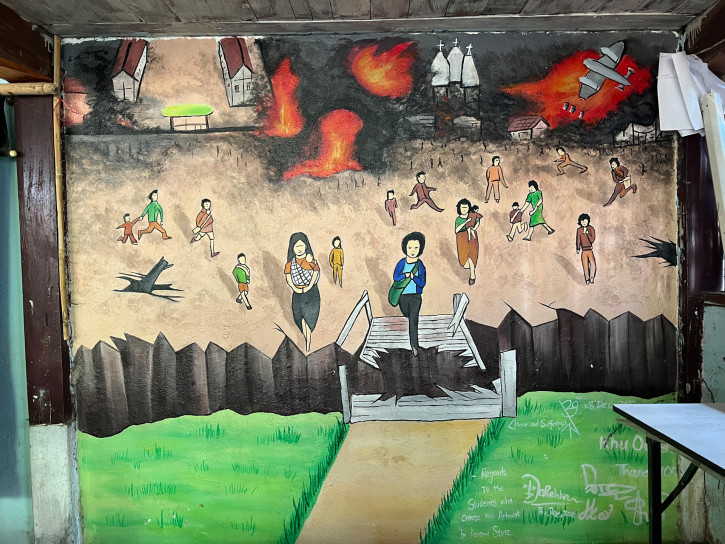

A mural at the Karenni Social Development Center is a stark reminder of the life these young people are escaping from.

REI (Formally RIJ – Refugees International Japan) has provided support for refugees since 1979 and, full disclosure, Eat provides the NPO with office space, which has also given us a lot more understanding of how they work and the projects they support.

It starts with something that is glaringly obvious – that refugees know best what their communities need and can do. They have the knowledge and skills to rebuild their own lives, but sometimes they just need some support, a ‘leg up’, to make that happen. That starts with listening and learning. There is a tangible effort to banish the spectre of the ‘white saviour’ approach of the past, where charities know what’s best and recipients are expected to be grateful.

"Refugees know best what their communities need and can do."

REI has a very lean approach, all funds are raised directly from companies and individuals, so minimum political influence, and close to 80% delivered to the projects themselves. With a maximum of US$25,000 awarded to any individual project per year, the NPO has funded more than 820 projects in over 20 countries worth cumulatively over US$11.5 million and impacted approximately 1,000,000 people.

“When you talk to people, don’t ask about their past, it will most likely be horrific and not something they will want to revisit. And whatever you do, don’t cry – this is not about you,” says Jane Best, Executive Director of REI as we begin our orientation to the field visit.

40 minutes from our hotel, but a world away from the life we’re used to.

We’re a group of seven sitting outside a small hotel in the town of Mae Hong Son, north-west of Chaing Mai. A destination for the more adventurous backpackers and part of the Mae Hong Son Loop popular with bikers, it still hasn’t quite sunk in what we will be experiencing in the next few days. Over the next few hours, we learn about the history – Burma being an outpost of the British Empire, the missionaries – many of the groups we will visit are Christian, and the politics – as always things are a lot messier than they seem from afar and, technically, what is a refugee anyway?

While most people understand a refugee to be a person who has fled their country due to fear of persecution, it is also a ‘status’ that needs to be given to a person by the UNHCR (The UN Refugee Agency) or the country that the person has fled to, assuming that they fulfil certain conditions and have the appropriate documentation. This status grants certain rights, such as not being sent back to the country from which they have fled. Most displaced people don’t have this status.

"...whatever you do, don’t cry – this is not about you."

Globally, the majority are actually IDPs, or Internally Displaced People. They haven’t left their country but have been forced to leave their homes and uproot their lives due to war or internal conflict.

Those that do cross borders, do so to find a temporary place of safety, with the intention of returning home in the future, or become asylum seekers – hoping for permanent relocation, with the challenge of arguing their case for official refugee status.

Then there are Stateless People, those considered to have never been a citizen of any recognised country. These include Kurds, Palestinians and Bihari (living in East Bengal/Bangladesh.

The Karen and Karenni people we’ll be visiting are not strictly stateless, they would be considered citizens of Myanmar, but effectively they are, and have no official refugee status either (Thailand is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention). So, they’re in limbo in ‘temporary settlements’ along the border, without equal access to health care and opportunities in work and education. They can’t go back and negotiate for some form of ‘official’ status, or resettlement is complex and subject to the whims and politics of the local government, police and military.

Maw Thya Mar and Khu Myar Reh update us on work at KSDC.

The following day, we head to KSDC, the Karenni Social Development Center. It’s 40 minutes from our hotel, but a world away from the life we’re used to. We move on to rutted dirt tracks, pass women washing clothes in the river and see the bars on our mobile flicker on and off.

KSDC describes itself as a small community-based organisation running training programmes for Karenni youth. The young people in question are mostly between 18 and 21, have all suffered human rights abuses, managed to escape across the border and now live in the temporary settlements – there is one close by.

We meet Khu Myar Reh, the principle and Maw Thya Mar, a senior trainer who take us on a tour of the settlement that has grown up around the center and give us the opportunity to meet some of the students.

Students introduce themselves and show off the English they’ve learnt.

The center runs a beginner and an advance course in a wide range of topics including Leadership, Human Rights, Democracy, Law, Environment, Community Management, IT, and English. The goal, as they describe it, is to ‘improve the lives of Karenni refugees and enable them to become advocates in non-violent social change and equipping them with the tools they need to help build a peaceful, democratic society, based on the rule of law.’

I get to talk to Par Myar, who is 19 and on the beginner’s course. In limited English she tells me that after completing this course she intends to go back to Myanmar to help her community, to be a strong female leader.

Then Maw Soe Myar, 21 on the advanced course. She talks about the coup and the fighting, leaving her family and traveling to the border during the rainy season. Like Par Myar, she also intends to go back after finishing her course, to be a teacher. To help educate and develop her community, she says. I ask how she feels about that – excited? Scared? “A bit scared,” she said, “but that’s normal. And, when I return, I will be stronger.”

Part of that strength comes from understanding how things can be. Many of these communities are very cut off from the rest of the world – internet is non-existent in many places, and cell phone reception, when available is limited. Maw Soe Myar said that she’d never met foreigners until she came to Thailand. Another said she didn’t understand the concept of ‘rights’ and didn’t think women had any, until she came to KSDC.

Maw Soe Myar: “When I return home, I will be stronger.”

We travel south to visit KWO – The Karen Women’s Organisation.

A bit of background: As a result of opposition group successes fighting on the ground, the government army retreated north towards the capital Rangoon. In its place the Junta now conducts bombing raids across the south of the country. We were told that whenever pilots see movement, they drop bombs, so whenever people hear planes, they hide. Their knowledge is detailed – the smaller jets have rockets, the bigger, slower planes have the bigger bombs. There are also 120mm mortar shells. Each sounds a little different and they learn to know what’s coming.

These raids destroy villages and kill families (One girl lost all her immediate family and only survived because she was visiting her grandmother). Those that get away, take refuge in the jungle – this includes pregnant women and those with young children. They have to build shelters, usually with palm leaves, and find food while having no access to proper medical services – clinics are a few hours away.

"A trip like this reminds you that refugees are real people and the majority of them don’t want to be in your country."

Add to that, there was severe flooding last year, followed by an insect infestation, so staples are in short supply, and we hear it is difficult to get seed to plant new crops.

Established in 1949, KWO promotes maternal health for women and families in Karen State in the south of Myanmar as well as seven refugee camps on the Thai Myanmar border.

With a staff of 18, the group create and distribute baby kits to over 1,200 women and babies. They travel by boat and motorcycle for up to three days to reach these people, learning their locations and needs by tapping into local women’s networks. Additionally, the group creates educational materials and run group sessions on nutrition, sanitation, hygiene and contraception. Many mothers don’t know how to spot symptoms of sickness, in themselves and their children, and there are a wide range of superstitions – such as eggs being bad for babies, or powder being better than breast milk– that need to be dealt with.

KWO is led by Naw K’nyaw Paw Nimrod, a strong, down-to-earth woman, who matter-of-factly updates us on the situation across the border, including the impact of the cut in US Aid. An additional part of their work is monitoring and reporting. People’s attention spans are short, and this is very much a forgotten conflict. All the more important to ensure it remains on the radar of governments and international organisations.

K’nyaw Paw’s own story is remarkable, but also typical of many of the people we meet – growing up she has had to push back against the pressure to fulfil a traditional woman’s role, to marry and start a family, and then turning down the opportunity of resettlement overseas to stay and support the needs of these women.

Umpiem Mae camp – a ‘temporary’ settlement that has been here for over 30 years.

We travel further south, towards Mae Sot. At times the road follows the Moei river, that naturally separates Myanmar from Thailand. Unguarded for much of its length, it is easily crossable. However, we now face regular check points. At most we are just waved through, but at one the police question what a bunch of foreigners are doing in this part of the country, and we get photographed, and our documents checked.

After a few more hours drive beyond Mae Sot we reach Umpiem Mae camp. At the entrance there is a large sign stating that this is a temporary settlement – in English – despite the fact that the camp has been here for over 30 years.

We’re here to visit an addiction programme run by DARE Network, an organisation co-founded by Pam Rogers, a very energetic septuagenarian from Canada. DARE is now running programmes in five camps and supported by REI.

Dare clinic at Umpiem Mae.

While visiting Thailand, Pam saw the trauma inflicted on people by war, the drugs trade and displacement and decided to do something about it.

She talks about generational trauma and addiction being a coping mechanism. Alcohol is one of the main problems, as well as betel nut and sometimes stronger drugs. Unsing a combination of acupuncture (specifically on the ears, we discovered, it’s known as ‘acudetox’), yoga, water immersion and group therapy, they run both residential and non-residential programmes of between 20-40 people mainly from the camps. In addition, they run a training programme for new team members, as well as general education and prevention program. So far, they have treated over 6,000 people, with a success rate of around 60% – this compares to an average of 25-30% in the west.

We meet Plaw Moo Hai, the head of the Umpiem Mae clinic, who used to be a addict himself, and a gang member (with the tattoos to go with it). He came to the clinic as a patient, successfully completed the programme and went on to train and join as a staff member.

Plaw Moo Hai, head of the Dare clinic at Umpiem Mae.

It’s clearly a role that suits him. He knows all the patients by name and checks in on their treatment between conversations with us. We hear about shame being a key driver for people coming to get treatment. In such a close-knit community, people don’t want to be a burden, whatever may have happened to them in their past. Pam and Plaw Moo both talk about giving people a sense of purpose being just as important as the medical treatment. Give a person responsibility for something and they have a reason to get up in the morning and pride in what they do.

We’re living in an increasingly fractured and radicalised world, where refugees are an easy target to gain votes – “we don’t want them over here.” A trip like this reminds you that refugees are real people and the majority of them don’t want to be in your country, they want to go back home to their culture and lead safe and productive lives. NPOs like REI help do that and, at scale, can help reduce the causes of displacement. So regardless of where you sit on the political spectrum, helping 120 million people better contribute to the economies of their countries can only be a win for everyone.

If you found this piece interesting, subscribe here to The Eat Digest - our monthly newsletter covering our latest insights, Japan brand and marketing news, and much more!