Running on Empty

Eat Issue 6: Gender

This article was originally published in August 2001.

Some of the odder animals on this globe can teach us a thing or two about crash diets.

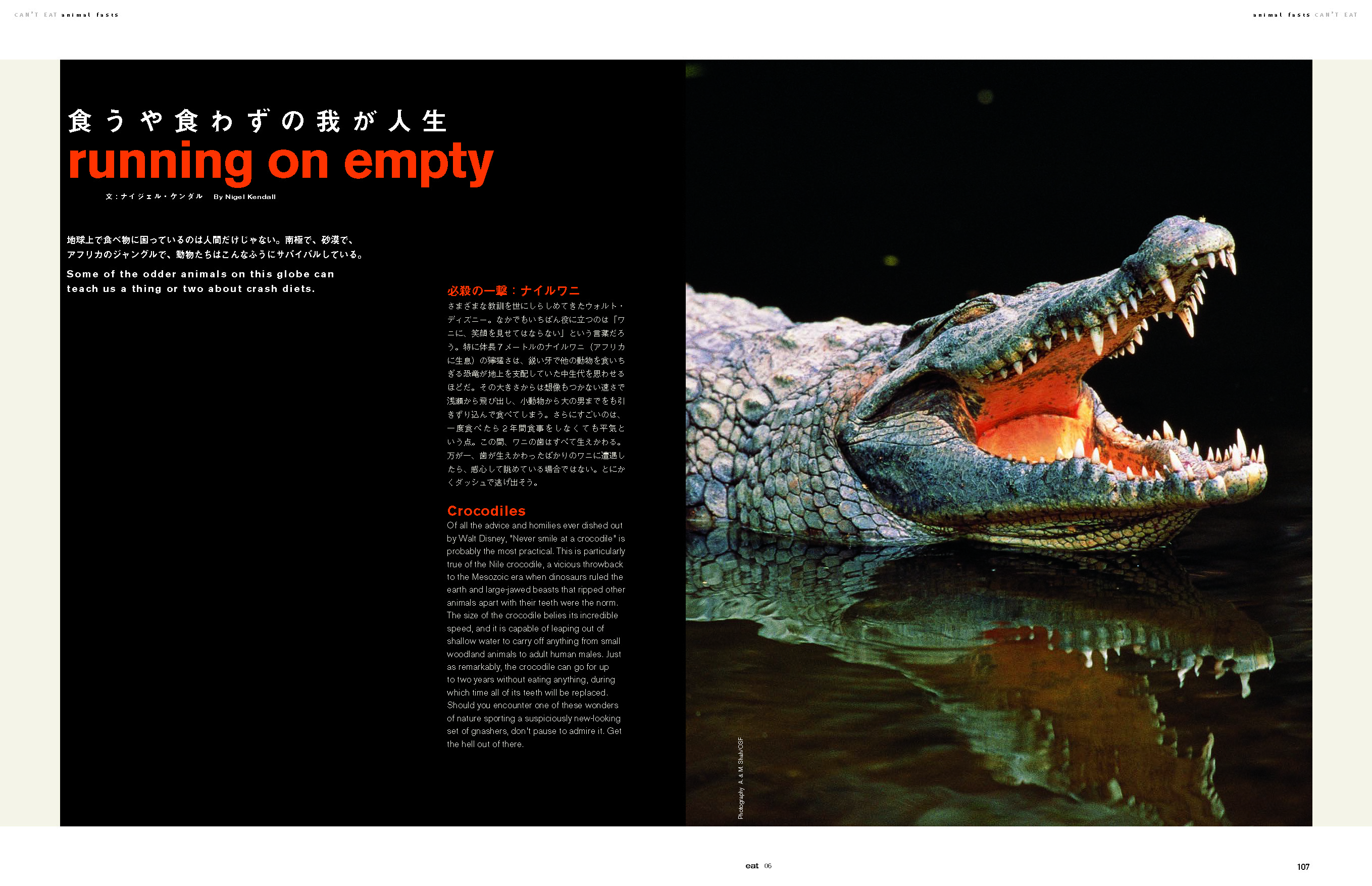

Crocodiles

Of all the advice and homilies ever dished out by Walt Disney, “Never smile at a crocodile” is probably the most practical. This is particularly true of the Nile crocodile, a vicious throwback to the Mesozoic era when dinosaurs ruled the earth and large-jawed beasts that ripped other animals apart with their teeth were the norm. The size of the crocodile belies its incredible speed, and it is capable of leaping out of shallow water to carry off anything from small woodland animals to adult human males. Just as remarkably, the crocodile can go for up to two years without eating anything, during which time all of its teeth will be replaced. Should you encounter one of these wonders of nature sporting a suspiciously new-looking set of gnashers, don’t pause to admire it. Get the hell out of there.

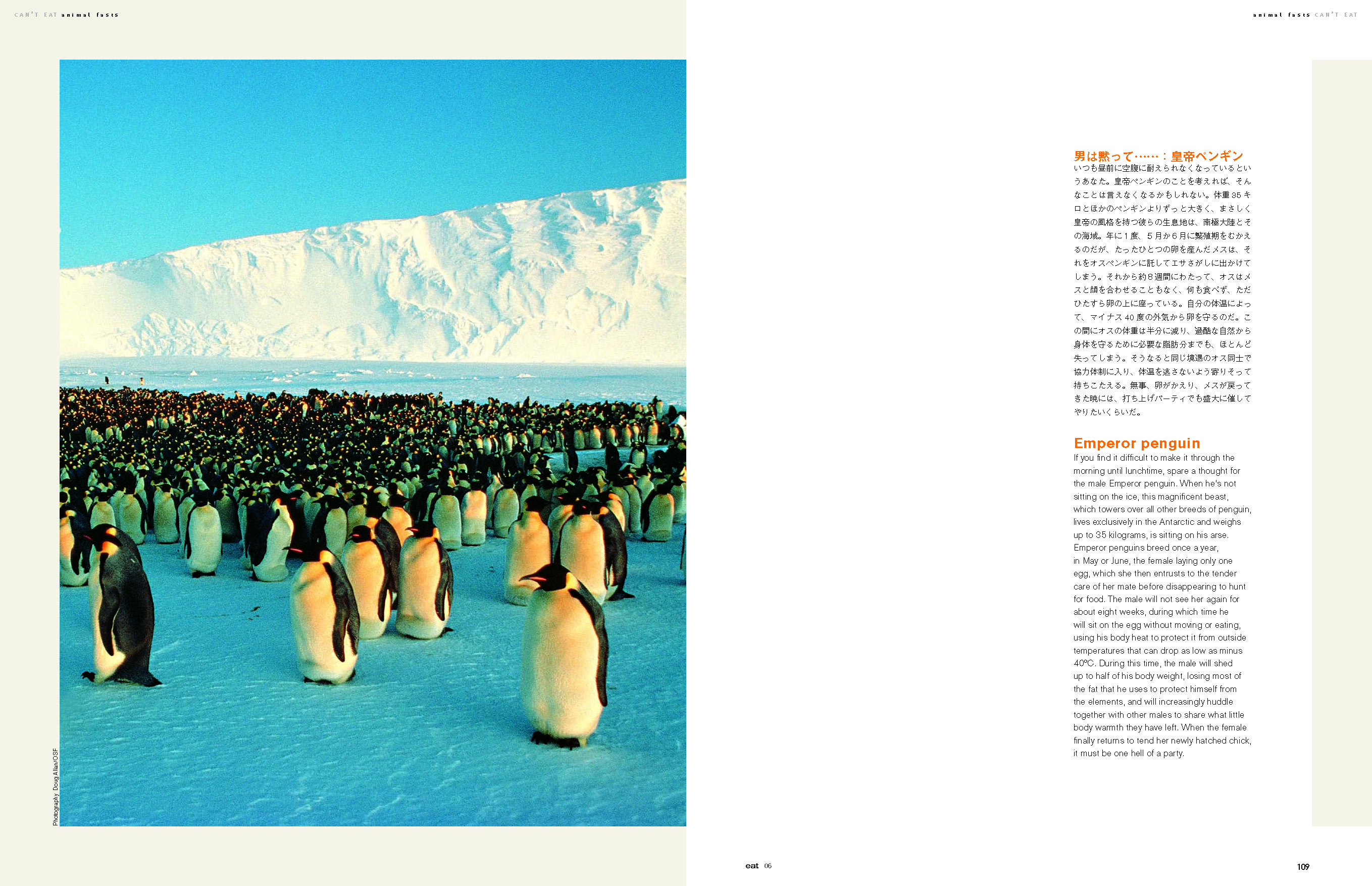

Emperor penguin

If you find it difficult to make it through the morning until lunchtime, spare a thought for the male Emperor penguin. When he’s not sitting on the ice, this magnificent beast, which towers over all other breeds of penguin, lives exclusively in the Antarctic and weighs up to 35 kilograms, is sitting on his arse. Emperor penguins breed once a year, in May or June, the female laying only one egg, which she then entrusts to the tender care of her mate before disappearing to hunt for food. The male will not see her again for about eight weeks, during which time he will sit on the egg without moving or eating, using his body heat to protect it from outside temperatures that can drop as low as minus 40ºC. During this time, the male will shed up to half of his body weight, losing most of the fat that he uses to protect himself from the elements, and will increasingly huddle together with other males to share what little body warmth they have left. When the female finally returns to tend her newly hatched chick, it must be one hell of a party.

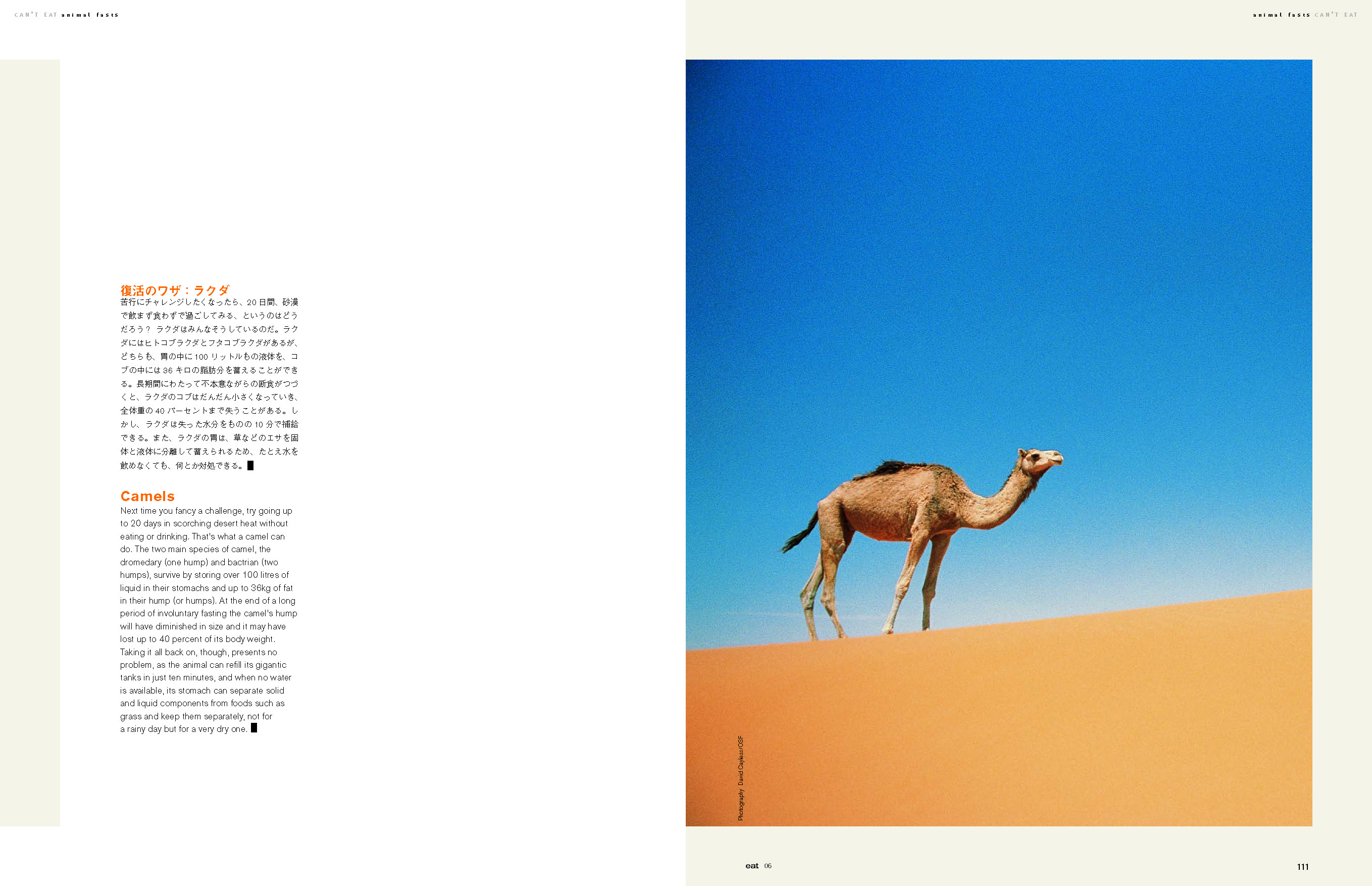

Camels

Next time you fancy a challenge, try going upto 20 days in scorching desert heat without eating or drinking. That’s what a camel can do. The two main species of camel, the dromedary (one hump) and bactrian (two humps), survive by storing over 100 litres of liquid in their stomachs and up to 36kg of fat in their hump (or humps). At the end of a long period of involuntary fasting the camel’s hump will have diminished in size and it may have lost up to 40 percent of its body weight. Taking it all back on, though, presents no problem, as the animal can refill its gigantic tanks in just ten minutes, and when no water is available, its stomach can separate solid and liquid components from foods such as grass and keep them separately, not for a rainy day but for a very dry one.

Text: Nigel Kendall / Photo: A. & M. Shah/OSF, Doug Allan/OSF, David Cayless/OSF